AKN Exhibition Travels from Accra to Cape Coast

Posted in July 2019 By Helen Bryant and Lennon Mhishi

Exploring the relationships that intersect heritage, memory and experiences of slavery past and present, a team from University of Ghana (UoG) worked on sites of historical slavery in the interior of the country as part of the Antislavery Knowledge Network (AKN). Moving away from the trodden path of the forts and castles on the coast, like Elmina and Cape Coast Castle, which are more frequently at the fore, understandably so, of conversations about historical slavery. Dr Wazi Apoh and Dr Benjamin Kankpeyeng from the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies carried out the work with assistance from Mark Seyram Amenyo-Xa, a PhD student.

In February 2018, the AKN held a workshop in Ghana, as part of the initiation of the pilot project with our partners at UoG. In , the AKN team at the University of Liverpool also hosted the UoG team, holding a workshop on mobilising the heritage of slavery to confront contemporary forms of exploitation. Various members of the Liverpool museum community, as well as scholars and other members of the public, engaged critically with the work of the AKN.

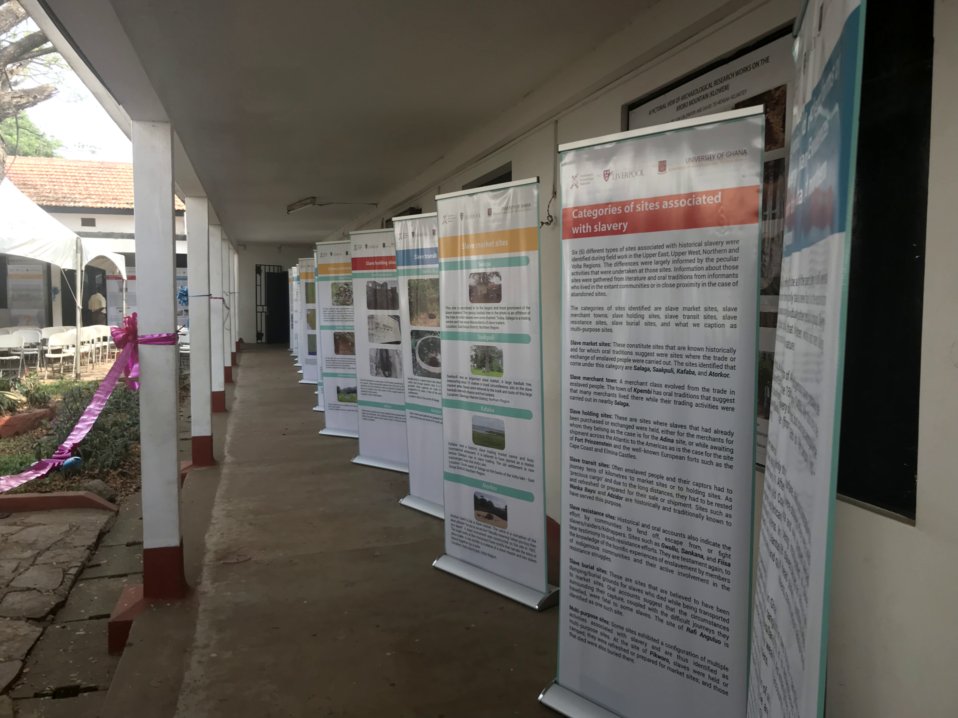

Following the end of the archaeological work in 2018, AKN team members from University of Liverpool made a visit to Ghana in 2019 to take part in the launch of an exhibition in Legon and also to travel around the country to see some of the sites used for this research. The exhibition maps and highlights specific sites of historical slavery in the interior and makes connections with wider AKN aims and objectives to address contemporary forms of enslavement.

From its introductory position at the Department of Archaeology at the University of Ghana, where it was mainly students who engaged with the display, the exhibition moved to the Cape Coast Castle for the month of April, where it was open to a different audience. This provided a wider community the opportunity to engage directly with the relationship of historical and contemporary slavery. By mounting the exhibition in a physical space that encapsulates the experience of the enslaved – the location became a part of the exhibition by encouraging visitors to relate to the histories of exploitation and provoke thought on slavery in the present.

The exhibition provided a platform to interrogate some of the tensions that accompany establishing relationships between historical and contemporary slavery, particularly at a local level, where some of the descendants of slave owners and the formerly enslaved live within the same communities, as was witnessed on part of our visit to historical slave sites in Salaga, GH. This also provides fertile ground to contest claims to a seamless continuity and comparisons on scales of suffering which diminish the complexities of the global relationships of hierarchy and power.

In addition to the social ramifications of the histories of slavery and their relationship to contemporary socio-economic realities, in our visit the team from University of Liverpool were confronted by the traditional and spiritual dimensions of the legacies of slavery when we were introduced to a local woman in Salaga, described as a “fetish priest”, who was said to often perform appeasement rituals on a space that is a slave burial ground. The memory of slavery and its hauntings in this way cease to exist as just material, yet this also reveals the kinds of investments communities have in engaging with the issues of slavery in the present, how they may be (mis)understood, and why it is crucial that these local communities, who have a complex understanding and relationship to slavery, past and present, be at the forefront of the conversations.

The exhibition, rather than being the end, or an end to the work in Ghana, is for the AKN a foundation to further the work and conversation, and evidence of the potential for mobilising memory and heritage in tacking contemporary slavery as a development challenge.

As the AKN continues work on its second phase, the exhibition as a living project can be allied with some of the work in Ghana, possibly travelling to other parts of the country, and even having lives in other countries. The material from the pilot project and the exhibition are important outputs, and our experiences provide lessons for the future of the project, and contemporary slavery work.

We hope that, with more feedback collected and reports of the projects available, the points of strength and the lessons to be learned will become more clear over the coming months as part of a monitoring and evaluation process.