On November 1 2024, a canopy collapsed in Novi Sad, Serbia, killing 16 people, sparking student-led protests against corruption. PhD student Sam Johnson spoke to several student protesters in Belgrade and Novi Sad. Read about his experience and his thoughts about what this means for Serbia in the future.

A culture of corruption

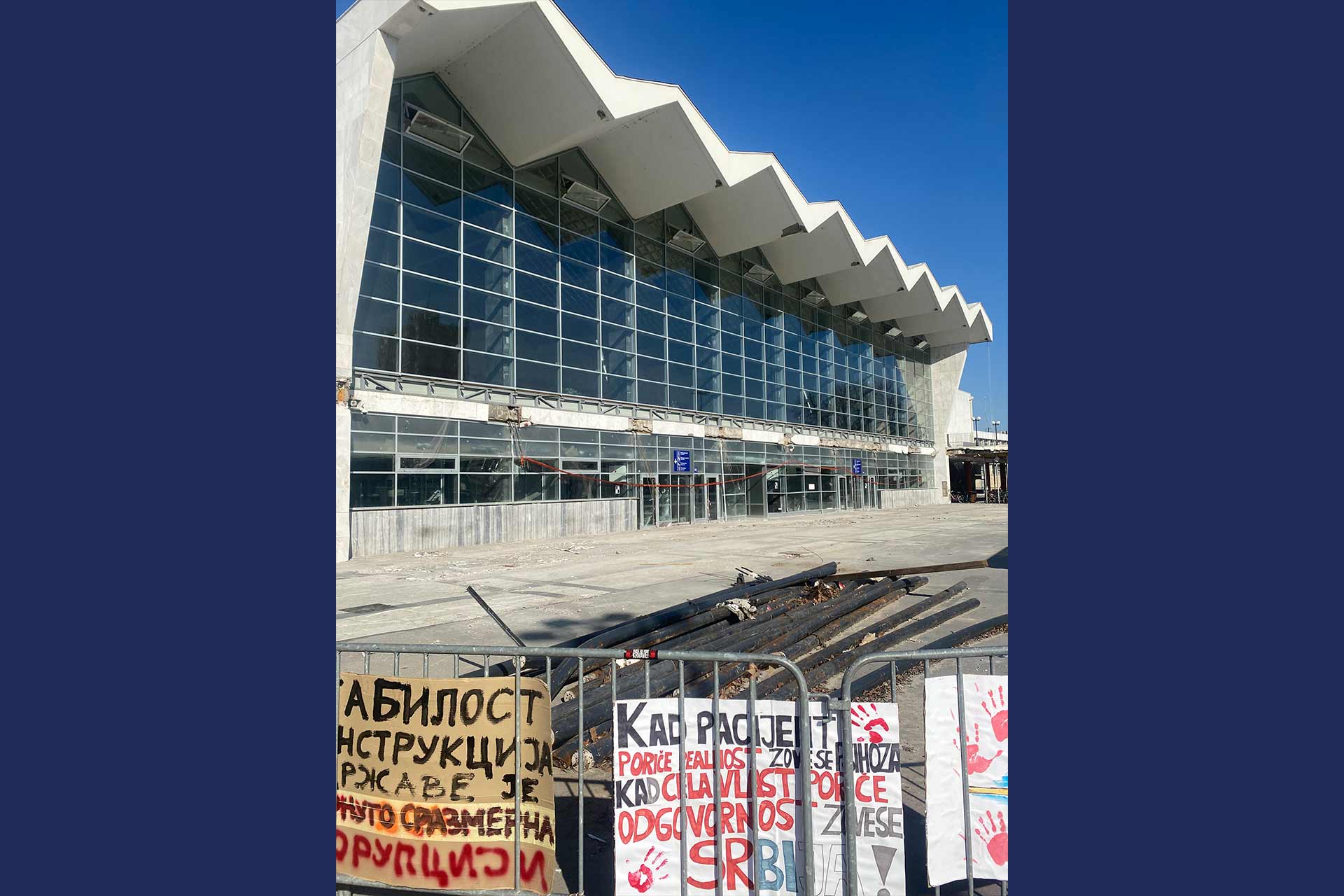

At 11:52am on the 1st of November 2024 a canopy collapsed outside the train station of Serbia’s second city, Novi Sad, initially killing 15 people, with one more tragically dying in hospital on the 21st of March from his injuries. A vigil was held in Novi Sad on the evening of the 1st of November which thousands attended to grieve together. Over the following days, weeks, and months this initial grief has evolved into anger and protests have developed across almost every Serbian town and city. Largely led by students, these protests have decried a culture of corruption which the demonstrators believe was directly to blame for this tragedy.

A student I spoke to in Novi Sad told me that “when the canopy fell, everything fell”. The events of the 1st of November have been a catalyst for a conversation that has needed to happen in Serbia for many years. The problems with corruption, nepotism and mistrust of government run deep. From the largest infrastructure projects and public institutions to the smallest family-owned businesses, corruption is an everyday fact of life. The students are ready to have that conversation and to challenge this culture of corruption. The question is: how much of society can they bring with them?

A national movement

These are now the largest protests in Serbian history, larger even than those in 2000 which led to the toppling of dictator Slobodan Milošević, a parallel often made by the protesters, and one all too clear to President Aleksandar Vučić who was a key advisor, communications officer, and minister to the former dictator. Every day protesters stand silent from 11:52am to 12:07pm, one minute of silence for each person killed in Novi Sad. On New Year’s Eve, instead of the usual fireworks and celebrations, thousands of protesters in Belgrade fell silent. From 11:52pm until 12:07am, they stood remembering those killed.

The students called for a general strike on the 24th of January and were joined by many small businesses and news organisations sympathetic to their cause, and to mark the three-month anniversary of the tragedy thousands marched the 80km from Belgrade to Novi Sad to hold vigil outside the station, being given food and water from the villagers they passed on their way. On the 3rd of February the legal profession voted for a 30-day strike in solidarity and support with the students, echoing the students’ concerns around corruption and effectively bringing the justice system to a grinding halt. And in a particularly poignant display of intergenerational solidarity, on the 5th of February hundreds of pensioners gathered in Trg Republike (the main square of Belgrade) in support of the striking students. This is not, as President Vučić would like to paint it, a protest only of students, but rather a protest led by students which is finding wide ranging support from civil society at large.

I visited Belgrade and Novi Sad in early February to witness the protests firsthand and speak to students involved. Standing among the crowds I was struck by the sight of hundreds of student marshals and stewards in high visibility jackets directing the protesters through their megaphones. At 11:52am a shout goes up from the marshal’s megaphones and the protesters stop and stand silent for 15 minutes; people lean out of their windows, shopworkers stand in their doorways and buses and trams grind to a halt around them, unable to pass through the blocked streets. There is a genuine youthful excitement at the heart of these protests and as they draw to a close the stewards form conga lines and celebrate another successful morning of protest whilst other students congregate around speakers and listen to music or distribute flyers detailing their demands and the government’s response.

However, there is a much darker undertone to these protests. Whilst the atmosphere on these protests is largely peaceful on the students’ side, they have been subject to attacks which have been linked to the governing party. Protesters have been run over and beaten on numerous occasions and this is why there are such a large number of stewards and marshals who keep an eye out for these attacks. The students I have spoken to are not only worried about attacks but also highly wary of intimidation and infiltration from the government, police and intelligence agencies, often agreed only to speak on the basis of strict anonymity such was their concern. Many spoke of examples of police intimidation of their co-demonstrators and there have been many allegations of highly sophisticated spyware being found on the phones and laptops of student organisers.

Stand off with the government

Despite all of this, in my conversations with many of the student protesters there is a resigned lack of immediate interest in the toppling of President Vučić and his government, something also noted by Guardian journalist Jullian Borger. Instead, they see this movement as part of a larger cultural and intellectual revolution happening in Serbia. President Vučić, since sacking his prime minister and the mayor of Novi Sad in an attempt to show justice was being done, offered to have an advisory (and non-binding) referendum on his presidency. This was rejected by the protesters. They believe that Serbian society is rotten to the core and that a change of government would likely do little to change the situation at large. Instead, they are making four specific demands:

- Publication of all documents relating to the reconstruction of the railway station in Novi Sad

- Confirmation by competent authorities of the identity of all persons who are suspected of having physically attacked students and professors, as well as initiation of criminal proceedings.

- Dismissal of criminal charges against arrested and detained students at protests, as well as suspension of already initiated criminal proceedings.

- Increasing the budget for higher education by 20%.

These specific demands have been a powerful tool in uniting a wide range of society, with often wildly different political ideologies and loyalties, behind the students. They are reasonable, well made, and devoid of all the usual political ideology that often takes over protests.

Usually in Serbia, left-wing liberals and self-avowed Marxist university students often march on the same protests as far-right nationalists. Pro-EU and anti-EU banners are held aloft alongside one another, anti-vax and anti-NATO slogans alongside orthodox iconography, anarchist symbols, and banners insisting on the ‘territorial integrity’ of Serbia and the reclaiming of Kosovo. What is unique about these protesters is how united they are around an almost singular message of anti-corruption and around these four demands. Students hold plenary sessions in their universities and vote on every suggestion and the whole process is extraordinarily well organised and democratic, if not at risk of becoming slightly bureaucratic according to some of the student organisers I spoke to. However, this is not to undermine their efforts; it is no exaggeration to say that these are some of the best organised student-led protests in history.

However, despite all of this, the protesters are still in a stand-off with the government. The government insists they have met all the student’s demands, and the students insist they have not. This has led to the government reverting to its usual playbook, and that of populists around the world, of painting the protesters as purely politically motivated and influenced and led by foreign agents. President Vučić has claimed repeatedly that the protesters do not represent the will of the true people of Serbia and has promised to govern for ‘all Serbians’.

Looking ahead

The question is, where do these protests go now? Long-term large-scale protests are nothing new in Serbia, protests following two mass school shootings in May 2023 went on for months decrying a culture of violence which the demonstrator’s thought endemic in Serbian society. But what is different about these protests is the disruption of daily protests and blockades. Students have been blockading their universities for since the 22nd of November, and they show no sign of letting up.

The students in Belgrade and Novi Sad that I have spoken to see these protests as the start of something larger; a cultural shift and intellectual revolution within Serbia. There is an underlying concern amongst many of the students I have spoken to about how this movement, with its very specific demands, is allowing the liberals and the right wing to come out against corruption together. However, they are not particularly united around much else. You don’t have to scratch much below the surface of these protests to find those same tensions which have always divided this country. This is something that President Vučić hopes to exploit. On the 19th of March his government – still led by Prime Minister Miloš Vučević – resigned. It is likely that snap parliamentary elections will be held in early June and President Vučić is hoping that these elections will expose and exacerbate the splits within the protest movement in an attempt to weaken them.

I have been struck by how this tragedy has started a conversation on corruption in Serbia that shows no sign of going away any time soon. Whilst these protests might not be the same as those that toppled Milošević in 2000, they are clearly the beginning of a cultural shift in Serbia, only time will tell how far it goes.

Sam's PhD thesis title is: The sources of national populism: a study of political views amongst youth in Serbia and Poland.