It’s a mad world: but these great thinkers may help you understand the current political mess

by Michael Hauskeller

Western democracies are in a state of crisis. The liberal world order that was created after World War II is crumbling and we don’t quite understand what is going on or what to do about it. Fortunately, some of the great literature and philosophy of the past can help us to make sense of it and maybe even to find a way out of the mess.

First of all, we need to give up the idea that the world is organised in a rational way. The world has not gone mad. It has in fact always been mad. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued that at the heart of everything – and that includes us – is not reason but blind will. This, he wrote, explains why the world is in such a sorry state and we keep messing things up by fighting needless wars and inflicting so much suffering on ourselves and each other.

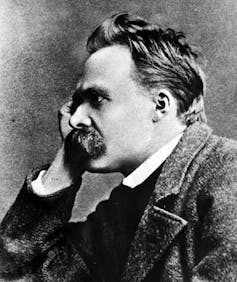

Herman Melville, author of the wonderful (and rather disturbing) novel Moby Dick, thought that our life was all a cruel joke that the gods play on us, and the best we can do is to play along and join their laughter. Friedrich Nietzschedeclared God to be dead so that we are now free to do as we please and to make our own will the measure of all things. The French philosopher and novelist Albert Camus described the world as an alien place that couldn’t care less about our human needs and wants.

What we can learn from these writers is that the first thing we have to do to make sense of what is happening in the world today is to stop believing that any of this is meant to make any sense. Madness is the rule – not the exception.

The need for chaos

In a mad world it is to be expected that people are generally quite mad too. This is the second thing we need to realise. We tend to assume that people do things and want things for good reasons. But very often we want things that it makes no sense to want because they are clearly harmful. When someone tries to reason with us, pointing out all the factual and logical errors we commit, we just ignore them and carry on as before.

This would be very puzzling if we were indeed rational animals. But we are not. We are certainly capable of being rational and reasonable, but the problem is that we don’t always want to be. Reason bores us. Occasionally we want and need a little bit of chaos. Or even a lot of chaos.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the author of Crime and Punishment and other great novels about a world that has lost its way, once remarked (in his 1864 novella Notes from the Underground) that people are generally “phenomenally stupid” and ungrateful. And he wouldn’t be at all surprised, he says:

If suddenly, out of the blue, amid the universal future reasonableness, some gentleman of ignoble, or, better, of retrograde and jeering physiognomy, should emerge, set his arms akimbo, and say to us all: ‘Well, gentlemen, why don’t we reduce all this reasonableness to dust with one good kick, for the whole purpose of sending all these logarithms to the devil and living once more according to our own stupid will!’

No doubt such a gentleman (and perhaps more than one) has now indeed emerged. Yet this is not the main problem. What is really offensive, according to Dostoyevsky, is that such a man can be sure to find followers. Because that is “how man is arranged”.

Creators and performers

Nietzsche, too, knew how easily we can go wrong and desire things that do not deserve to be desired and admire people that do not deserve to be admired. In Thus Spake Zarathustra he writes:

In the world even the best things are worthless without someone who performs them: those performers the people call great men. Little do the people understand what is great, namely that which creates. But they have a taste for all performers and actors of great things.

Our problem is that we idolise the performers and not the creators, those who only pretend to make things great again and to get things done, and who are very good at convincing others of this without actually doing anything great at all. The performer, Nietzsche says, has:

Little conscience of the spirit. He believes always in that which makes people believe most strongly - in him! Tomorrow he has a new belief, and the day after, one still newer. Quick of perception is he, like the people, and his moods change. To upset is what he means by ‘prove’. To madden is what he means by ‘convince’. And blood he deems to be the best of all reasons. A truth which only slips into subtle ears he calls a lie and a nothing. He indeed believes only in gods that make a great noise in the world!“

And what now?

So is there anything we can do about all this? How do we deal with a world that is clearly off-kilter? How do we keep our sanity in a world that seems to be getting more insane by the minute? Various coping strategies have been proposed by our great writers: Schopenhauer thought we should find a way to negate the will and turn our backs on the world for good.

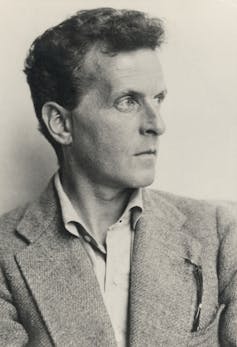

Melville suggested amused detachment, Marcel Proust an escape into the world of art. Tolstoy found meaning and solace in faith, Dostoyevsky in universal love and Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in being grounded in God. Nietzsche thought we should embrace and love whatever happens to us, and Ludwig Wittgenstein believed that we should live in and for everything that is good and beautiful.

But to change the world we may need a more active and combative approach. Instead of trying to escape from or accept what is happening, we can also – as Camus suggested – create a more meaningful world by becoming rebels and fighting injustice in all its forms. Such a rebellion can be quite modest in scope. It does not have to be loud and flashy. Not much more may be required from us than being and remaining – despite all the challenges we face today – decent and reasonable people.

The following passage from an address that William James gave in 1897 on the occasion of the unveiling of the Robert Gould Shaw American civil war monument in Boston sums it up quite nicely:

The deadliest enemies of nations are not their foreign foes, they always dwell within their borders. And from these internal enemies civilisation is always in need of being saved. The nation blest above all nations is she in whom the civic genius of the people does the saving day by day, by acts without external picturesqueness; by speaking, writing, voting reasonably; by the people knowing true men when they see them, and preferring them as leaders to rabid partisans or empty quacks.

Amen to that.

Originally published in the Conversation.