I’m British, but never thought too patriotically about that knowing that my father’s ancestors invaded from Normandy in 1066. My mother arrived more recently, in 1938. She was German and did not approve of her government. She escaped in a hurry and was welcomed in England with an immediate offer of British citizenship. My childhood home was continually populated by folk from all over the world. ‘My country right or wrong’ never made sense to me, an internationalist.

In the early 1970s, studying for my geology degree, I learnt that burning fossil carbon must, inevitably, lead to global warming. I stayed in academia and pursued a career in the oil industry, but becoming part of the problem wasn’t for me.

Global warming is well under way; over 1°C so far, more than 2°C inevitable and further warming dependent on how effectively we can mitigate. For millions, perhaps billions, migration will be the adaptation of necessity.

It is well documented that climate change associated with the 2001 – 2010 drought, probably the worst drought in the Fertile Crescent since agriculture was invented in the Neolithic, was a contributory factor in the Syrian civil war. The resulting refugee displacement has led to crises across Europe and contributed to the UK’s EU referendum result.

During 2016, I was inspired by other press photographs to paint representations of the plight of refugees. The first was a group caught up on the Greek-Macedonian border, the emotions of anger and despondency on the faces as they stand behind the razor-wire. It is based on a photo published in Der Spiegel on 3rd of March 2016. The caption read: “With countries across the Balkans now severely restricting the number of refugees they are allowing to cross their borders, the Balkan Route is all but closed off. The result has been a huge backup in Greece. Here, refugees demonstrate behind a fence on the Greek border with Macedonia.” The photographer is unknown, the only attribution being to AF—Agence France-Presse.

Razor-wire. Oil on board 45 x 60cm

Razor-wire is material that has received scant attention. First produced in World War I in the form of barbed tape, it used less steel than traditional barbed wire, but it was not until the late 20th century that it became widely used for security, usually reinforced with a central strand of high-tensile steel wire, the barbed tape crimped onto the wire. It was only after the 9/11 attacks of 2001 that razor wire became the material preferred by the military but it has now become the iconic fence of repression.

Barbed wire at least has the merit of practical value to stock farmers as a cheap and effective means of controlling cattle, who view the grass greener on the other side of the fence. Razor wire, however, has only ever had one purpose: to allow some people to control the movement of other people.

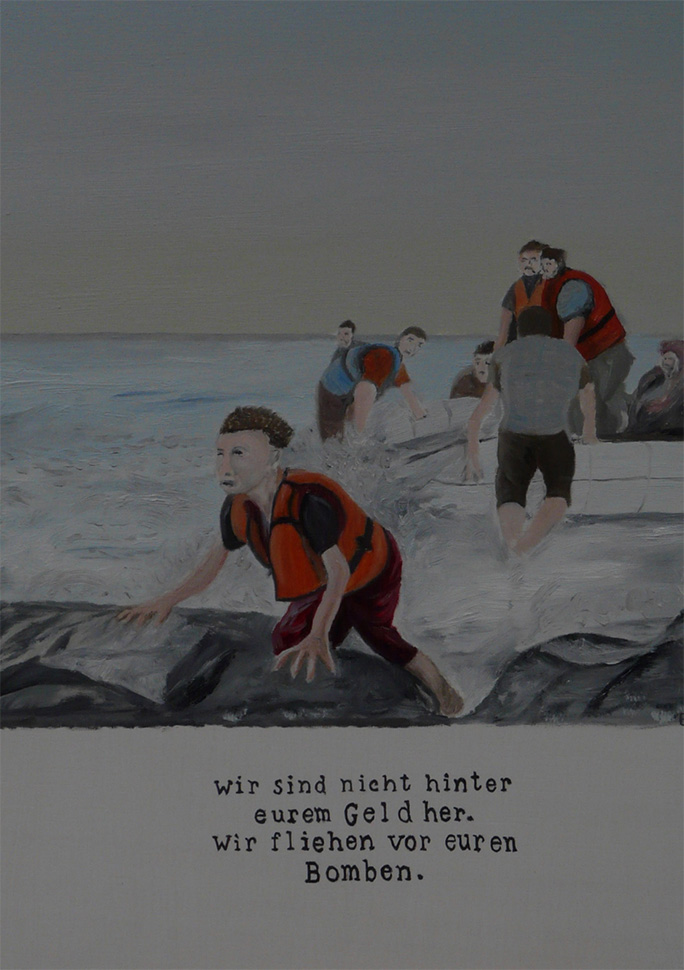

Wir Sind. Oil on board 55 x 42 cm

My second painting in the refugee series was again based on a press photo, but I don’t know the originator. It was widely distributed as a meme on social media with the words explaining that the refugees were here, not for our money but to flee our bombs. The young boy scrambles onto the rocks of his promised land, alone and apprehensive for the future but as yet unaware of just what kind of welcome that awaits.

Arrival on the Island of Lesbos, summer 2016. Oil on board 45 x60 cm

This painting was based on a photo by Achilleas Zavallis published by UNHCR. Fearful children are carried to safety by rescuers in control of the immediate situation. Their longer-term future is unknown.

Waiting. Oil on board. 38 x46 cm

A photo by Marko Djurica for Reuters and published in the Observer in January 2017 provided the inspiration for this painting of refugees queuing for food in Belgrade. Grey blankets offer little insulation from the exceptionally cold winter.

What can artists do? Maybe not much; Picasso’s Guernica didn’t prevent war, but everything we do is a political act, if only by omission. We choose whether to paint a pretty landscape, a bunch of flowers or a war zone. I was struck when visiting the Open Exhibition at the newly re-opened Ferens Gallery in Hull, City of Culture, that not a single one of the works appeared to have any obvious political content. All was safe and uncontroversial. Was this a deliberate policy of the judges or just a reflection of a zeitgeist in which art is regarded as escape from the tough end of life rather than a commentary on it? In the next room hung some of Francis Bacon’s Popes. They’d have been rejected had they been entries in the Open!