Dr Toby Hall

Topics in the dynamics of surface homeomorphisms

In topological surface dynamics, we study the iteration of homeomorphisms f:X->X of topological surfaces X, and in particular the orbits of points x of X, which are the (bi-infinite) sequences (f^n(x)), where f^n denotes the n-fold iterate of f (or the -n-fold iterate of f^{-1] if n is negative). x is said to be a period n point if f^n(x)=x, and n is the least positive integer for which this is the case.

Questions studied in topological dynamics include: what periods of points are there? How does the number of period n points behave as n goes to infinity? Are periodic points dense in X? If we "know about" a single periodic orbit (or a finite number of them), what can we deduce about the dynamics of f as a whole? What is the topological entropy (a measure of "chaos") of f? Can we get a lower bound on it from information about a few orbits of f? In the case of surfaces such as the annulus and the torus, what is the rotation set of f (i.e. at what speeds can points rotate around the surface under iteration)? In what ways can the answers to all of these questions change as we vary the homeomorphism f continuously? In what ways do they change in specific families of homeomorphisms?

Such questions can be asked in any dimension, but are particularly interesting in dimension 2. In one dimension the theory is very well developed and is largely combinatorial. The theory in two dimensions has a much more topological flavour, since there is room in X for the points of the same or different orbits to "knot around" each other in non-trivial ways. In three or more dimensions there is too much room, and the answers to many of the questions above are either trivial (knowing about a few orbits of f tells us pretty much nothing), or prohibitively difficult.

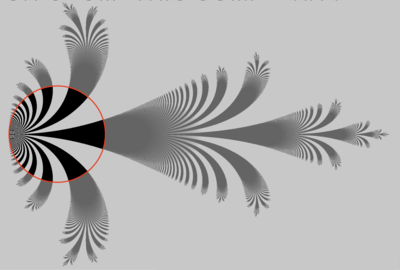

The key result which has driven much of the research in this area for the last 30 years is Thurston's classification of isotopy classes of surface homeomorphisms, which states that every surface homeomorphism can be deformed into ("is isotopic to") a homeomorphism g which is of one of three types: reducible, which means that the surface can be cut into topologically simpler pieces on which g acts independently; finite order, which means that g^n is the identity for some n; or pseudo-Anosov, which means that g preserves a transverse pair of singular measured foliations, stretching uniformly along one and contracting uniformly along the other: this produces chaotic dynamics which can nevertheless be studied very precisely using combinatorial techniques ("train tracks" and "Markov partitions"). Moreover, a pseudo-Anosov has minimal dynamics amongst all the homeomorphisms isotopic to it: therefore, if one can show that the homeomorphism f one is interested in is isotopic to a pseudo-Anosov g, then one obtains a calculable lower bound on the dynamics of f. I have broad interests within this general field: questions which interest me particularly at the moment are the study of "generalized pseudo-Anosovs", which are like pseudo-Anosovs but their invariant foliations can have infinitely many singularities; the study of rotation sets of torus homeomorphisms; and the use of Dynnikov's coordinate system to carry out explicit calculations on the boundary of Teichm\"uller space (roughly speaking, on the space of measured foliations).

Please feel free to contact me to discuss possibilities.

The following are possible project titles:

- Dynamics of generalized pseudo-Anosov maps.

- The action of horseshoe braids on Dynnikov coordinates.

- Rotation sets in families of torus homeomorphisms.

Dr David Martí-Pete

I am interested in studying the iteration of holomorphic functions that are transcendental, that is, with at least one essential singularity. The easiest class of such functions are transcendental entire functions, which have one essential singularity at infiniy which is omitted, like the exponential function. In my PhD, I specialised in the iteration of transcendental self-maps of the punctured plane, which have two essential singularities at zero and infinity which are omitted. However, in the recent years, I have been interested in problems related to wandering domains, which are a type of Fatou component that under iteration never returns to a place that has been before.

The following are a sample of possible research topics:

1. Iteration of transcendental self-maps of the punctured plane

A transcendental self-map of the punctured plane $\mathbb{C}^*=\mathbb{C}\setminus\{0\}$ is a holomorphic function from $\C^*$ to itself for which both zero and infinity are essential singularities. Such functions arise in a natural way when one studies the complexification of analytic circle maps. Such functions share many properties with transcendental entire functions but at the same time have some differences that, in my opinion, make them an interesting class of functions to study.

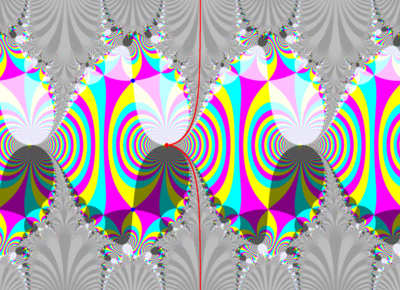

The complex Arnold standard family is the most famous family of transcendental self-maps of the punctured plane. It consists of perturbations of a rotation on the circle. Arnold used this family to study the dependence of the rotation number of an orbit with respect to the parameters. This gave rise to the so-called Arnold tongues, which are regions of the parameter space where this rotation number is constant. This family plays an important role beyond complex dynamics as it is often used as a model for phase-locking phenomena in dynamical systems. In a work in progress with Mitsuhiro Shishikura, we study the complex version of the Arnold tongues, and many questions remain open about such sets.

2. Wandering domains of transcendental entire (or meromorphic) functions

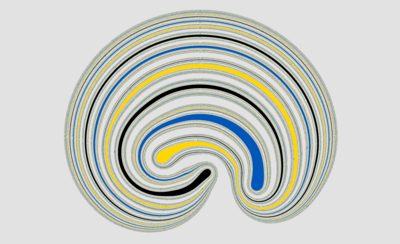

The Fatou set (also known as the stable set) of a meromorphic function is the largest open set on which the family of iterates of the function is defined and normal. A wandering domain is a connected component of the Fatou set that does not become periodic eventually; in other words, they never return to a place where they have been before. By a result of Sullivan, polynomials and rational functions do not have wandering domains, but Baker proved that transcendental entire functions do. In a recent joint paper with Lasse Rempe and James Waterman we proved that wandering domains can be quite interesting from both a topological and dynamical point of view: (1) wandering domains can form Lakes of Wada, that is, infinitely many disjoint wandering domains can have the same boundary; (2) escaping wandering domains can have non-escaping points in the boundary. Many questions remain open about these elusive Fatou components.

3. Fractal dimensions and computational complexity of Julia sets and subsets thereof

For a transcendental function, the Julia set (where chaotic behaviour takes place) is a fractal set. Thus, it is a very classical question to study their fractal dimension (e.g. the Hausdorff dimension or the packing dimension). One of the recent breakthroughs in transcendental dynamics is Bishop's result that the Julia set of a transcendental entire function can have Hausdorff dimension 1, which is the smallest possible value. In a couple of ongoing collaborations, we study the dimensions of different subsets of the Julia set: (1) boundaries of basins of attraction, and (2) hairs (also known as dynamic rays), which are curves to infinity along which pints escape to infinity. One question that I find interesting is to study the dimension of the set of points that escape but are not fast escaping (compared to the iterates of the maximum modulus).

A different way to measure how complicated a Julia set can be is to look at its computational complexity. In complex dynamics, we often draw pictures of Julia sets by asking a computer to iterate a collection of points (one for each pixel) for a finite number of times and predict whether it will escape or not. However, if the function is transcendental, due to Picard's theorem this is not an easy task. Can we rely on such pictures? Roughly speaking, a set is computable (e.g. in polynomial time), if a computer can produce arbitrarily good approximations of the set in a given time that depends only on the accuracy. In a joint work with Artem Dudko, we study the computational complexity of Julia sets of functions in the exponential family. It would be interesting to study the complexity of Julia sets of other classes of transcendental functions.

If you are interested in any of these topics or would like more information, please feel free to contact me.

Dr Daniel Meyer

A holomorphic map $f$ in the plane preserves angles at every point $z$ that is not critical (i.e., $f'(z)\neq 0$). This conformality is the geometric reason behind many of the surprising results in complex analysis. By the Riemann mapping theorem conformal maps are plentiful in the plane. On the other hand, they are very rare in higher dimensions.

Quasiconformal maps, and the closely related quasisymmetric maps, are maps that may change angles, but only up to a fixed multiplicative amount. These maps have become one of the most important tools in complex analysis. In addition, they provide an analog to conformal maps in settings where there are no conformal maps. Finally, such maps appear naturally in geometric group theory.

The quasisymmetric uniformization problem asks when a given metric space is quasisymmetric to a given standard space. Very often the metric spaces that appear in this question are coming from a dynamical system. It turns out that in many instances quasisymmetric uniformization is equivalent to the question whether the dynamical system acts conformally. Of particular interest is the question when a metric 2-sphere is quasisymmetrically equivalent to the standard 2-sphere. This is closely connected to Thurston's classification of rational maps as well as Cannon's conjecture.

Here are some possible topics for Ph.D. projects:

1. Quasisymmetric unformization

One question is to decide whether certain classes of spaces can be quasisymmetrically uniformized. Another question is to investigate the properties of known quasisymmetric maps.

2. Thurston maps

Recently the monograph "Expanding Thurston maps", jointly written with Mario Bonk, appeared. However, many open questions remain, in particular how these results can be extended to the non-expanding setting.

3. Matings and unmatings

Mating is an operation that "glues" the dynamics of two polynomials together, to form a new dynamical system. Often, but not always, this results in a rational map. To decide when this is in fact the case is a difficult question. Unmating is the reverse procedure, i.e., geometrically decomposing a rational map into two polynomials. In both cases, there are many interesting open questions.

Back to: Department of Mathematical Sciences