This research blog by PhD researchers Lucy Moynihan and Michelle Girvan, explores Liverpool Institutions and their Legacies of Slavery. Lucy and Michelle help us understand the complex legacies within institutions like the Blue Coat Hospital and the Liverpool Athenaeum, shedding light on the city's complex past.

Growth and the Atlanic trade in Liverpool

There are many historic sites across Liverpool which can trace their origins to the eighteenth century. During this period, Liverpool grew rapidly from a small town of about 7,000 people in 1708, to a wealthy mercantile port town of 83,000 people by 1801. Much of this population explosion, and wealth accumulation was brought by Liverpool’s Atlantic trade. The town’s shipping was dominated by vessels used to transport enslaved African people along the middle passage, from the west coast of Africa to the Americas. On their journeys back to the Mersey from the violent world of the plantation societies, Liverpool ships brought back goods which were produced by enslaved labour. The rum, tobacco, sugar and cotton that were offloaded onto the docks fed capital and profits straight into the hands of Liverpool’s wealthy merchant community.

The Blue Coat and Athenaeum

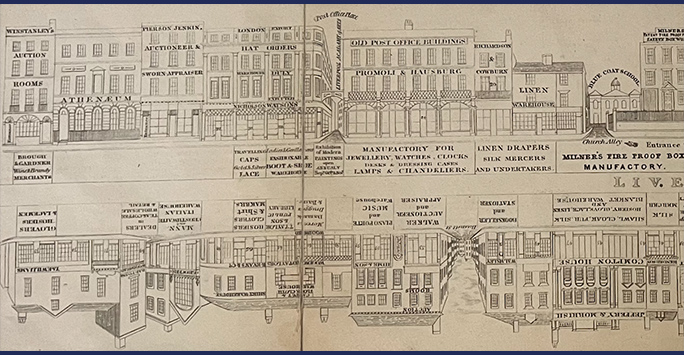

Enslavement and colonialism seeped into all aspects of Liverpool society in the eighteenth century. The capital generated was reinvested into charitable and cultural institutions, such as the Blue Coat Hospital (17) and the Liverpool Athenaeum (1797). The Blue Coat was built as a charitable school for Liverpool’s orphaned children, at the end of Church Alley, where the historic building still stands today. The Athenaeum was built just round the corner, as an all-male subscription library and newsroom towards the top of Church Street. Both sites were less than a mile away from Liverpool’s wet dock and were central meeting points in the networks of Liverpool’s enslavers. The two sites were projects of collaboration, connected spatially, and through their cross-proprietorship – shown in our network map below. By approaching our respective PhD projects into these institutions collaboratively, we have been able to demonstrate that Liverpool enslavers were key players in the foundation of Liverpool’s oldest private members club and subscription library, and the oldest eighteenth-century building in the cityscape today.

Gaining insights

By taking a record of paying subscribers to both institutions for one year (1803), we found 194 individuals who were present at both the Blue Coat and the Athenaeum. By using the Voyages database, we have calculated that 76 of these subscribers were known traffickers of enslaved people. Men like Jonathan Ratcliffe, Thomas Staniforth, and George Case trafficked an inconceivable number of African captives with a horrific ease. They reinvested their violent profits into these Enlightenment institutions, distancing themselves from the image of Liverpool merchants as ‘getting money at all events’.

Working collaboratively on the troubling histories of these two Liverpool institutions, has brought new insights into the entanglement of enslavement with cultural and charitable pursuits. The damage that was caused by calculating Liverpool merchants to the lives of African people on the other side of the Atlantic cannot be undone. This was, in the words of Kris Manjapra, an ‘incalculably traumatic system of genocide’, which went beyond two hundred years of slavery, to the ongoing legacies of racism in the present. We hope, that by building on this collaborative approach alongside other Liverpool researchers and heritage sites that are exploring their legacies of slavery and colonialism, we can begin to re-write these histories and focus on the ‘possibilities of repair’.

Find out more

You can find out more about our collaborative research from our poster which will be displayed at the HSS PGR Showcase on the 5th and 6th March. If you are interested in joining our collaborative network, which focusses on Liverpool’s Colonial Legacies, please send us an email at liverpool.legacies@gmail.com.

About the authors

Michelle Girvan is researching Charity, Piety and Commerce: The Liverpool Blue Coat School and Pragmatic Politeness, 1708–1796.

Lucy Moynihan is researching Race, Slavery and Abolition at the Liverpool Athenaeum & Beyond, 1797-1833.