Dr Robin Whelan discusses the parallels between The Traitors and late antique Church councils.

This blog was first published on Substack.

In January 2025, The Traitors is coming back for new seasons in the UK and US. The competition series pits traitors against faithfuls in this addictive, unscripted show. I love it, but I think its producers have made a terrible mistake. It should clearly be called The Heretics.

Sure, the titular villains are ‘traitors’. Three contestants are secretly chosen to undermine the collective goal of earning a pot of shared prize money through group tasks. These traitors pretend to be ‘faithful’, but their aim is to steal this money for themselves. Each night, they ‘murder’ one of their fellow contestants. If the faithful identify all of the traitors before the series ends, they win; if any traitors are left when the game ends, they walk away with the cash.

US trailer (UK trailer is at the end):

This hunting out of subversives within the group is a familiar feature across various historical contexts; it is exactly what late ancient Christians sought to do. Early Christian writers thought they had ‘heretics’ in their midst. The term itself comes from haeresis (or ‘choice’). Originally it was used for philosophical schools, but now applied to particular Christian thinkers, their theological ideas, and their followers. These heretics were seen as dangerous people who sought to lead their fellow Christians away from salvation by convincing them to adopt false beliefs or practices. In this way, they too sought to deceive the ‘faithful.’ These were the fideles: the community of baptized Catholic Christians.

In reality, those condemned as heretics in late antiquity were as arbitrarily chosen as the otherwise polite British people tapped on the shoulder by Claudia Winkleman (in the BBC version) and the rather more sharp-elbowed reality TV regulars selected by Alan Cumming (in the US version). Ancient heretics were, as far as modern scholars can tell, sincere individuals who thought that what they believed and did was right. Whether it was Arius, Priscillian, or Nestorius–or the ‘Arians’, ‘Priscillians’ or ‘Nestorians’ who supposedly followed them instead of Jesus Christ—accused heretics in the late Roman world were not trying to be ‘traitors’. They simply lost out in politicized debates over doctrine and practice. Yet almost all Christians—even ‘heretics’—agreed these evil people existed; they just disagreed on who they were. The Traitors stages these debates in real time and underscores how it can irreparably rupture social groups. The ‘faithful’ tear themselves apart as they try to identify the enemy within.

These accusations are aired in the portion of the game which comes closest to emulating early Christian debate: the roundtable. At this daily meeting, the players level allegations and interrogate one another before taking turns to vote on who to banish from the game as a suspected traitor.

This exercise strongly resembles a church council: an assembly where bishops would seek to solve theological disputes by formulating a new statement of faith and excluding those whom they decided were heretics. These meetings became a standard part of the governance of the church, whether they were ecumenical (empire-wide) councils like Nicaea (325), Rimini and Seleucia (359), Ephesus I (431), Ephesus II (449) and Chalcedon (451), or provincial or local gatherings. The minutes (acta) of many of these councils survive. They are some of the most precious documents of the ancient world insofar as they (at least claim) to provide the verbatim transcripts of face-to-face conversations. They give us the sense that we are watching Christian debates play out in real time.

The social dynamics between Church Councils and Traitors roundtables are eerily similar and equally messy. Although the bishops were ostensibly supposed to meet in a peaceful atmosphere inspired by the Holy Spirit, the surviving minutes suggest these verbal exchanges frequently led to ad hominem attacks and kangaroo courts. And that is just what made it into the acta. Those who lost the debate, or simply said something they later regretted, claimed that the participants had been subject to violence. So, some of the participants at Chalcedon (451) explained away their (diametrically opposite) theological statements at Ephesus II (449) by suggesting they had been coerced; dissenters had been attacked by imperial soldiers, over-zealous monks, and even their fellow bishops. (The BBC and NBC have better crowd control.) Just like the roundtable, conciliar sessions would often end with a series of ‘subscriptions’: speeches where individual bishops explained their vote to banish a particular heretic or ban a particular doctrine.

Participants in the roundtable adopt similar strategies to early Christian bishops, and run up against similar problems.

In late antiquity, those who were too keen to hunt out heretics in their midst were at risk of denunciation: both because their opponents would make counter-accusations, and because sowing division was the sort of thing a heretic would do. This dynamic plays out in The Traitors as well. Suspicions have repeatedly fallen on contestants who throw out names of potential traitors. In season 2 of the UK series, Zack was marked for his constant ‘theories’, and even Harry and Jaz’s reputation as successful traitor-catchers brought them under increasing suspicion as time went on. As a result, many of the faithful—both in late antiquity and in the tv castle—simply go along with whatever the majority has decided and parrot arguments (however unconvincing) rather than risk drawing attention to themselves by airing their own accusations.

But going along to get along has its own dangers to navigate. Just as rapidly changing definitions of orthodoxy caught out bishops at Ephesus II (449) and Chalcedon (451), so the shifting suspicions of the contestants can latch onto insincere or inconsistent statements. Above all, the players at the roundtable—like bishops in councils—know that what they are saying is being recorded (if by cameras and microphones as opposed to notaries). Participants who are swayed by the party line again and again risk looking shifty by trying to fly under the radar, both to their fellow players, and to the audience at home.

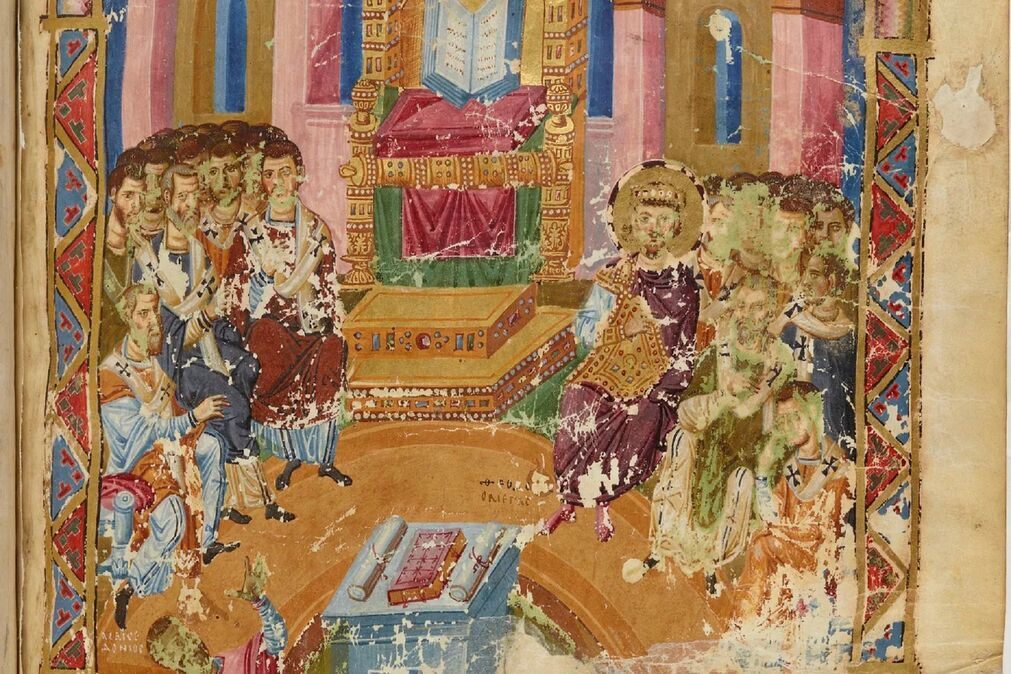

Manuscript BnF Grec 510 (Homilies of St. Gregory of Nazianzus), folio 355 recto. Miniature of the First Council of Constantinople (381CE). The emperor Theodosius I and a crowd of bishops seated on a semicircular bench, on either side of an enthroned Gospel Book. An heretic, Macedonius, occupies the lower left corner of the miniature.” (caption and image via Wikimedia).

That audience is increasingly critical of the mediated version of events which reality television provides us. Producers carefully cut their raw footage to establish compelling narratives. The gap between these constructed storylines and what ‘really happened’ creates ample room for speculation. In this sense, reality TV viewers show themselves to be experts at source criticism. Here again, the import of editing and omission can be seen in ancient councils as well. Recent work on the minutes of church councils has shown how their compilers edited the transcript to leave out everything from dissenting voices and inopportune statements to acts of coercion and violence. Above all, the (highly partisan) presiding bishops shaped this (supposedly verbatim) record to make the case that those condemned were clearly heretics. Producers always have an angle and intent. What are the Acts of the Council of Aquileia (381) or Ephesus (431) but a ‘villain edit’?

My analogy between ancient heresy and The Traitors only goes so far. Conflict over orthodoxy and heresy was not just a game: for bishops, it could result in deposition, excommunication and penal exile. ‘Losing’ had real social consequences (and not just the opportunity to start a podcast). More than that, there was no big reveal at the end, except, perhaps, at the Last Judgment. Still, as Season Three’s premiere looms on the horizon, I would argue that analysis of late ancient doctrinal controversy gives us useful ways to understand what is going on in The Traitors—and vice versa. Although we don’t have video of the actual accusations thrown out at late Roman Church Councils, we do have a kind of sociological laboratory for understanding how suspicion, trust, alliances, accusations of treason, and constructions of faith can divide groups—and ultimately result in discord rather than orthodoxy.