In the days leading up to and on 23 August, International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade, we will post each part of a three-part blog series by Melissa Jeannot. This blog series explores the complexities of the slave trade in Columbus, Georgia.

Part 1 - The Market

The sun beams down on you relentlessly in the open roofed slave pen. Your head is filled with the sounds of children crying and mothers shushing; unable to distinguish if the noise is echoing off the 10-foot-high brick walls or the memories of the auction that brought you here. You stare out of an iron window grate. Your eyes look ahead scanning the environment beyond the bars: a busy street, carriages, a trader’s coffle of fresh slaves coming from the North and a red flag signaling the selling of enslaved people (Flanders, 1933; McInnis, 2011).

Dread, agony and exhaustion flood your chest with the acceptance of where you are and what's about to happen. Cramped in a small dirty yard with so many other enslaved men, women and children you understand - this is the market, and you are the product.

The Columbus slave market

The market I am talking about is one I have become quite familiar with while working on a Masters’ Research Internship Scheme project (‘Sold Without Consent’: advertisements for the sale of enslaved people in US historical newspapers’) with Dr. Stephen Kenny at the University of Liverpool. It is the slave market of Columbus, Georgia specifically in the years of 1857 through to 1861. This was one of many slave markets throughout the Deep South of the United States. The window pictured at the top belongs to one of the prominent slave traders in Columbus, Georgia named A. K. Ayer, who notoriously had a slave pen constructed with walls topped with broken glass to prevent slaves from escaping (Telfair, 1929). Ayer was one of three major “Negro Brokerages” conducting business in Columbus during those years: along with Harrison & Pitts and Hatcher & McGehee (Carey, 2011). These three brokerages all ran successful slave trading businesses in the bustling downtown of Columbus, creating lucrative alliances and competitive rivalries.

These three brokerages ran successful businesses and learned to read the market in enslaved people well. The traffickers trading in Columbus were savvy businessmen with lots of experience in the slave trading business; they could predict the demands of Columbus clients and supply the ‘perfect’ human stock. Historian Walter Johnson has researched the ways in which enslaved and trafficked people altered their appearance and behaviour to make themselves more, or less, attractive to certain buyers at auction, to control a small aspect of their fate. Slave-borne knowledge of traders and planters was passed around in jails and slave pens and could potentially save the enslaved from appealing to the wrong sort of buyers (McInnis, 2011). Unfortunately, these tactics probably didn’t work with Ayer, Harrison & Pitts and Hatcher & McGehee as they knew what they and their enslaver clients were looking for.

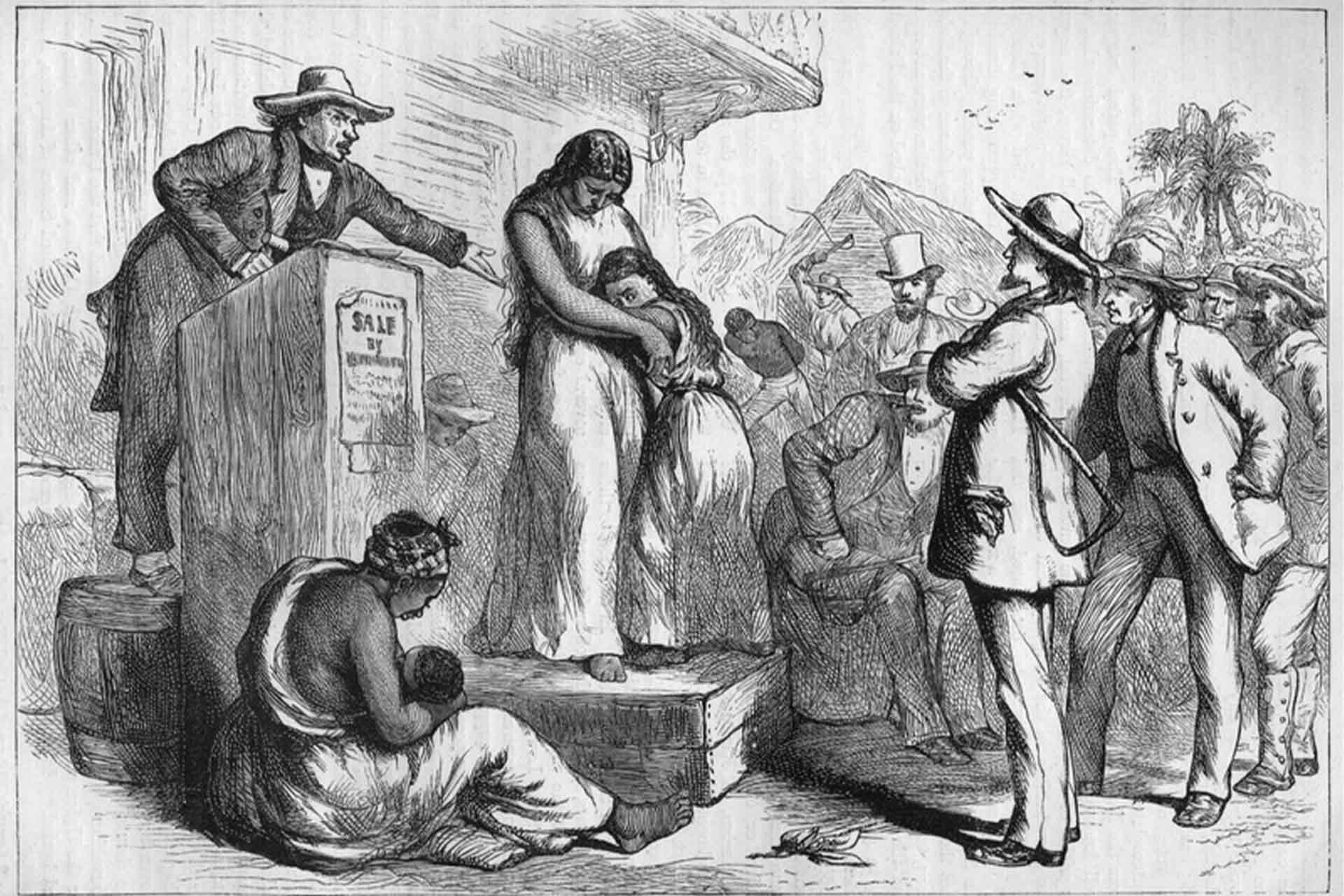

"A Slave Auction" Edmund Ollier, Cassell's History of the United States (London, 1874-77), Vol.3, p. 199.

Enslaved women and children in the trade

Anthony Gene Carey’s book Sold Down the River notes that some enslavers in Columbus were looking for good, able-bodied male labourers, but many were also looking to purchase women and children. Enslaved women and children provided domestic and other valuable labour for the white families that lived in the town (2011). This led to the increase of enslaved women and children being brought in from outside of Columbus. We can see some evidence of this in the Hatcher & McGehee slave book that was recovered from the years of 1858 to 1860 and made available in the somewhat obscure journal Muscogiana (1993), women and women & children’s groups were bought and sold by Hatcher & McGehee than men; with the highest recorded sale going to Minerva and six children. The group was bought for $3200 and sold at $4000 for a total profit of $800.

Importing from Virginia

It was from Virginia that many enslaved people were bought and trafficked to Georgia. In numerous slave accounts collected from the Federal Writers’ Project: “Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Georgia, Part 1'' ex-slaves recalled knowledge of such forced journeys made by their own mothers, showing evidence of this demand for the import of enslaved women and children (1936). Martha Colquitt recounts that her mother “wuz born in Virginny, and her and my grandma wuz sold and brought to Georgia when ma wuz a baby” (1936, pg. 248). Similarly, Benny Dillard says that “dey brung [his mother] from Virginny and sold her down here in Georgy when she was jus’ ‘bout 16 years old” (1936, Pg. 297). It was on the backs of these women and their infant children that slave traders like Hatcher & McGehee profited most.

First image A. K. Ayer's Slave Pen Window.

In part 2, The Mirror, we'll look at how traders' actions reflected the broader societal values of the time.