Were you dazzled by Daphne Bridgerton's debutante dress in 'Bridgerton'? With its wardrobe of high waistlines and puffed sleeves, this hit show has made Regency fashion - and the idea of #regencycore - a key trend in 2021. We spoke to museum curator, Pauline Rushton, to find out what fashion was really like in the early 19th century.

"The popular Netflix series Bridgerton is set in the world of the early 19th century aristocracy, and the elaborate costumes in the show have been the focus of much media attention and online debate. But what was fashion really like during that time?

The period between 1790 and 1820 was one of great social, political and economic change. There were also a great many changes to fashionable dress, partly influenced by events happening around it.

Just like today, people then used dress as a way of displaying their wealth and social status. The emerging middle classes, in particular, used fashionable dress as a marker of their rising social position in society. Through their clothes, they marked themselves out as part of an upwardly mobile social group, and reflected their individual tastes.

New technology speeded up changes to fashionable dress at this time. Developments in the spinning, weaving and printing of fabrics made them cheaper and more accessible to greater numbers of people. As a result, fashion gradually filtered down the social scale and was not reserved just for the wealthy.

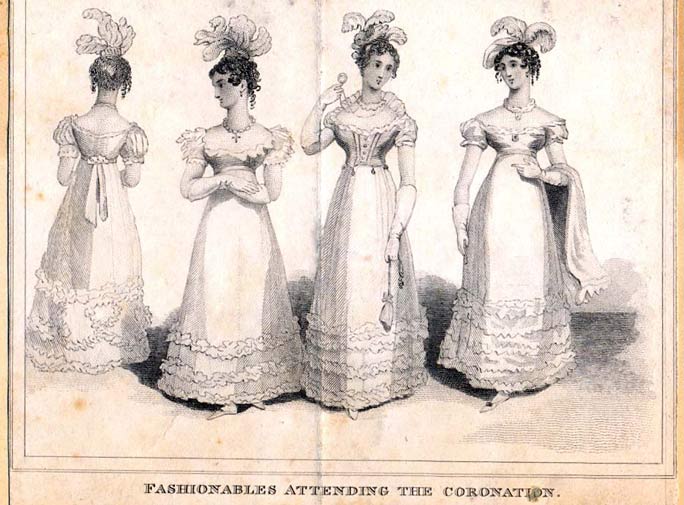

Women in white dresses for George IV's Coronation, 1821

Between 1800 and 1810, white was the most fashionable colour for dresses. It continued to be popular in the following decades, especially for young women, largely because it was associated with purity and innocence. As the novelist, Jane Austen, commented in Mansfield Park in 1814, ‘A woman can never be too fine while she is all in white’. White cotton muslin, embroidered with white thread or left plain, was the height of fashion. The finest muslin was imported from India in great quantities.

To some degree, fashion was influenced by the garments carved on the fine white marble statues that had been recently re-discovered in the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome. Such excavated pieces were illustrated and published for wider public appreciation.

Echoing this statuary, women’s high-waisted, low-necked, sleeveless gowns, often with only a simple shift beneath, revealed their arms and the outline of their bodies. It was said that some women even dampened their dresses to make them cling to them, revealing even more of their shape, although documentary evidence for this is largely lacking. The pure white of a dress was often enhanced by a brightly-coloured accessory, such as a silk shawl, a sash or a parasol.

Such flimsy dresses and few layers of clothing offered little protection from the elements, and women wore a range of accessories to keep warm in cold weather. They included the spencer, a short, fitted, long-sleeved jacket of silk or wool, and the pelisse, a coat with a high waistline. The diarist, Parson Woodforde, commenting on the unseasonably inclement weather in June 1799, noted that ‘It was very cold indeed today, so cold that Mrs Custance came walking in her spencer’. The spencer is thought to have originated as a man’s tail-coat and to have taken its name from the second Earl Spencer who, while out hunting on horseback one day, is said to have torn off the tails of his coat while jumping a fence.

Evening dress, silk net, repro silk under-dress, circa 1817-20.

Hooded cloaks were also worn, especially by the less well-off, and fur wraps known as tippets. Shawls, made from fine cotton muslin or wool, were worn throughout this period. Cashmere shawls, woven from the wool of Tibetan mountain goats, were originally imported from the Kashmir region of India. When the Napoleonic wars disrupted their trade routes, limiting the supply, weavers in Norwich, Edinburgh and Paisley began to make them from sheep’s wool. Early shawls were rectangular in shape but over time they became square. Their traditional motif was the buta or pinecone, which began as a small border pattern and grew gradually larger. Eventually this design, and the shawls themselves, became so associated with Paisley in particular that they were named after the town. Indeed, the generic term, Paisley shawls, is still widely used today.

An alternative to the pure white dress was one of printed cotton. From the 1770s onwards, improvements in spinning and weaving processes speeded up the production of cotton and made it cheaper. Cotton had previously been hand-printed using engraved wood blocks, which was labour intensive and expensive, but in the 1780s the process became mechanised. By the 1790s, cotton for dress fabrics was being printed on machines fitted with engraved copper cylinders or rollers. This greatly speeded up production and made cotton increasingly affordable. It soared in popularity because it was cheap and easy to wash. From the 1790s until the 1840s, cotton was the most fashionable fabric for dresses. After that period, it was replaced by silks, and cotton was worn mainly by working class women and domestic servants.

Pauline is Head of Decorative Arts and Sudley House at National Museums Liverpool and is a key contributor to our Eighteenth Century Worlds research centre.

Discover more

Explore the fashion collections at National Museums Liverpool.

Find out more about history research at Liverpool.

All images courtesy of National Museums Liverpool.