The printed face is just the beginning of a 3D revolution

Dr Chris Sutcliffe, Centre for Materials and Structures, writes

The news that a man in Wales was able to have his face reconstructed after a serious motorbike accident has brought the wonder of 3D printing to the mainstream. It’s the result of changes in regulation and improvements in the technology and is the start of something much, much bigger.

The use of a combination of CT scanning and 3D printing methods to treat patients who are suffering from injury or defect is incredibly powerful. As has happened in Stephen Power’s case, it allows expert surgeons to manipulate the precise geometry of the patient’s face or other part of the body before the operation. That means the necessary parts can be designed and manufactured in a normal, albeit slightly compressed, design timescale.

Power suffered a number of impact injuries in his accident, he broke his cheekbones, top jaw and nose and fractured his skull. Several months later, doctors printed a symmetrical model of his face using CT scans and were then able to create implants and plates to rebuild his features.

But the majority of the techniques used to help Power have actually been around for decades. A very similar story to this was detailed in a BBC documentary nearly 20 years ago.

The fundamental patents that have been held for 20 years – including a particularly important piece of intellectual property owned by 3D printing company Stratasys – have now expired. That means that we are likely to see 3D printing really come into its own. These patents largely covered the manufacturing processes involved in 3D printing and now that this knowledge is no longer locked up by companies, people like Power can benefit more easily.

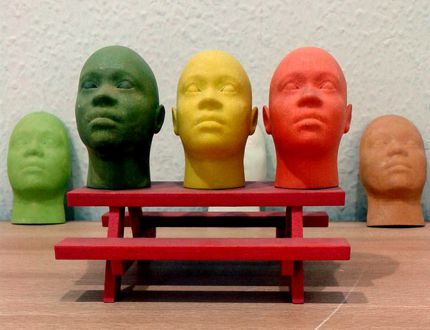

It has meant that low-cost 3D printing machines can be produced, enabling a better-served marketplace to emerge and a community of print-at-home enthusiasts, designers and innovators to get to work. They are printing toys, jewellery and even prosthetics.

But the hold up has also been about technology. Innovation in the field, and particularly in metal 3D printing, has really sped up in recent years.

Metal 3D printing produces components in biocompatible materials such as titanium from 3D data produced by a design system or CT scan. In the past five years these machines have improved to such an extent that they can now be used to make implantable parts.

The University of Liverpool built the first metal 3D printer in the UK, which has led to the production of implants for dentistry, orthopaedics and even veterinary treatment. And now the progress of 3D printing technology is gathering pace and this is largely due to more people being able to access and experiment with the devices in a variety of settings.

We’re likely to see a lot more stories like Power’s facial reconstruction in the future. For every wonder application that succeeds there are likely to be more failed ideas that never catch on but now that people all over the world can try things out, the possibilities are enormous. It will mean that 3D printing will be an every day occurrence and a normal way to treat patients rather than front page news.

This article can be found in The Conversation