Liverpool scientists construct molecular knots

Published on

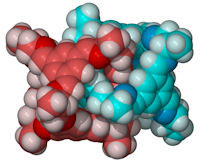

[caption id="attachment_10373" align="alignnone" width="200"] The molecular 'knots' have dimensions of around two nanometers[/caption]

The molecular 'knots' have dimensions of around two nanometers[/caption]

Scientists at the University of Liverpool have constructed molecular ‘knots’ with dimensions of around two nanometers (2 x 10-9 nm) – around 30,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

Most molecules are held together by chemical bonds between atoms – ‘nano-knots’ are instead mechanically bonded by interpenetrating loops. Liverpool scientists have managed to create nanoscale knots in the laboratory by mixing together two simple starting materials – one a rigid aromatic compound and the other a more flexible amine linker.

This is an unusual example of ‘self-assembly’, a process which underpins biology and allows complex structures to assemble from more simple building blocks. Each knot is ‘tied’ three times: that is, at least three chemical bonds must be broken to untie the knot. A single knot is a complex assembly of 20 smaller molecules.

Professor Andrew Cooper, Director of the University’s Centre for Materials Discovery, said: "I was amazed when we discovered these molecules; we actually set out to make something simpler. A complex structure arises out of quite basic building blocks.

"It is like shaking Scrabble tiles in a bag and pulling out a fully formed sentence. These are the surprises which make scientific research so fascinating."

The experimental work was led by Dr Tom Hasell, a Postdoctoral Researcher, who recognized that the data in an experiment to create organic nanocages was anomalous. In particular, the mass of the molecules was twice as high as expected, a result of the complex mechanical interlocking of two molecular sub-units. The team is now focusing on the practical application of these molecules and similar structures – for example, to build molecular ‘machines’ which can trap harmful gases and pollutants such as carbon dioxide.

The research, which was published in the journal Nature Chemistry, forms part of a broader five-year programme focusing on the synthesis of new materials for applications such as energy storage and conversion. The project is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Notes to editors:

1. The University of Liverpool is a member of the Russell Group of leading research-intensive institutions in the UK. It attracts collaborative and contract research commissions from a wide range of national and international organisations valued at more than £98 million annually.