It’s World Blood Donor Day, and we wanted to let you know how we use blood, donated by healthy volunteers, within the Centre of Excellence for Long-acting Therapeutics (CELT) and how it’s helping to eliminate devastating diseases around the world.

What is World Blood Donor Day for?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) designated 14 June as World Blood Donor Day and every country worldwide celebrates it. World Blood Donor Day “serves to raise awareness of the need for safe blood and blood products and to thank voluntary, unpaid blood donors for their life-saving gifts of blood.” – WHO

2024 marks the 20th year of WHO celebrating giving and they’re using the 20th anniversary to celebrate the lifesaving contributions of donors. Today is a platform for them to highlight regular donations' impact and the necessity of universal access to safe blood transfusions.

The UK National Health Service (NHS) has used World Blood Donor Day as a springboard to make this National Blood Week. They aim to get people talking about their blood types and open the conversation about why knowing your blood type is a helpful tool in understanding the impact you can have by donating. “There's a particular need for Black African, Black Caribbean and younger donors to ensure we can double the number of donors with the rarest blood types. This will enable better-matched blood types for patients in the future and reduce health inequalities.” – NHS: Blood and Transplant

Why do CELT support World Blood Donor day?

CELT’s work in long-acting therapeutics often requires human blood for our research and to test new medication formulations before further trials. Blood donation is critical to our work, so we wanted to use today to give back and show our commitment to such a necessary and convenient way to volunteer support to the NHS and UK’s medical research. While many of our staff are committed blood donors, we also thought we could provide insight into what some blood donations are used for within global health science.

When you donate blood at an NHS blood donation centre, one of the boxes you tick is to say that you understand your donation may be used for research purposes and CELT is one of the places that uses some of the small selection of blood marked for research.

However, CELT predominantly uses donors who come to the University and donate small samples directly to our research. Sometimes, if those two options are exhausted, we’ll buy blood from the non-clinical issue (NCI) team at NHS Blood and Transfusion (NHSBT), who provide donor blood as a not-for-profit service.

How do CELT’s use donated blood?

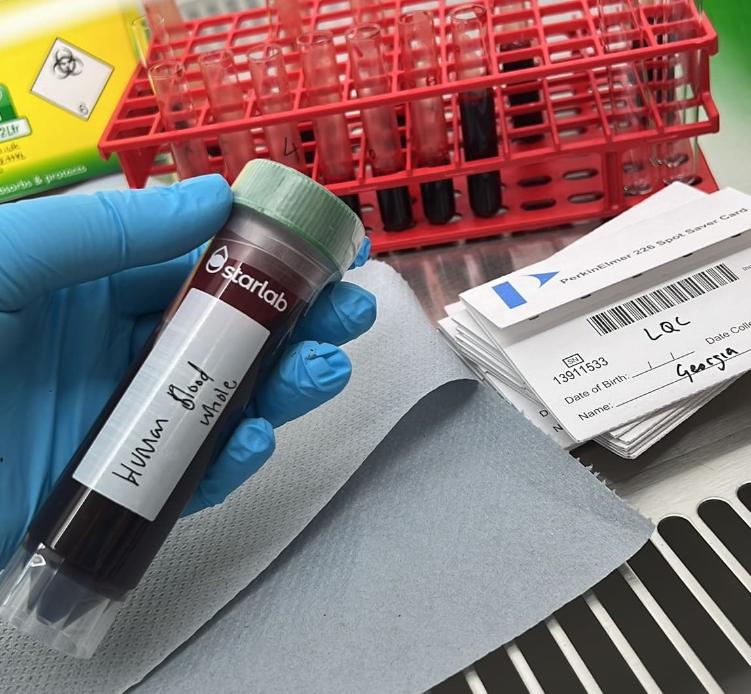

We spoke to Prof. Neill Liptrott, who leads the Immunocompatibility Group within CELT, and two PhD students within CELT, Georgia Duffy and May Al Adwani, whose research utilises volunteer blood donations as model systems, to discuss work they have undertaken to provide an insight into what we use it for.

What CELT projects do you use blood for, and how?

Neill Liptrott

We use blood across several CELT and CELT-related projects. Most recently, the National Institute for Health (NIH)-funded ‘Polymers of Prodrug’ project is developing long-acting formulations of antiretrovirals into implants inserted under the skin. Obtaining fresh blood from donors, instead of blood banks, is critical to our research to ensure the cells and proteins within it are as viable as possible. Although we examine lots of different routes of administration, healthy volunteer blood underpins many of our projects, as we can isolate and differentiate lots of immune cell types from it.Our most recent work is investigating the immunomodulatory potential of niclosamide and other mitochondrial uncouplers that may be suitable for use as long-acting therapeutics in SARS-CoV-2, Dengue fever, multiple sclerosis and cancer, all conditions that would see a significant improvement in patient quality of life via long-acting medication options. Investigating how they affect peripheral blood cells is key to their activity in preventing unwanted immune responses.

We use static and dynamic (mimicking peripheral blood flow) exposure systems to determine how individual immune cell types and relevant mixed cultures respond to advanced therapeutics and complex medicines such as long-acting injectables. We have developed many assays and models to study immunological responses, such as multi-colour flow cytometry, secreted bioactive molecule assessment, functional responses, cellular health, and intercellular communication.

Georgia Duffy

In my research, I’ve used blood for the Long-acting antipsychotics for mental ill-health in pregnancy and postpartum (LAMP) project where CELT are quantifying the drug concentration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in pregnant and post-partum women. Patient samples are collected on dried blood spot cards from finger pricks. (You can read a blog by Georgia about the LAMP project here)

Blood is used to develop liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry quantification assays by spiking blood with the drugs of interest. Once the assay is validated, the spiked blood will be used to determine the concentration of the drugs in a person’s blood.

Within my work, we use human whole blood to do red blood cell partitioning of different drug compounds. The blood is spiked with the drug of interest, then the spiked blood is radio-labelled to determine the blood-to-plasma ratio.

May Al Adwani

Within my work, we use human whole blood to do red blood cell partitioning of different drug compounds. The blood is spiked with the drug of interest, then the spiked blood is radio-labelled to determine the blood-to-plasma ratio.

What does donated blood help you achieve in your research?

Neill Liptrott

Although we use a lot of human immune cell lines in our work, primary blood, blood products, and cells more closely represent the responses one would see in the body. Peripheral blood is easy to obtain via our trained phlebotomists and it is critical that the blood is as fresh as possible. We and many others in the field have shown it to be a good model for determining immune responses and providing cells for our more complex tissue models. Additionally, we see much better “real world” responses in volunteer blood; we know that immune responses can vary for several reasons, and it is an active part of our research to determine which groups of people may be more or less susceptible to adverse reactions, and compatibility issues.

Georgia Duffy

We need blood to match the matrix the participants samples will be, it’s important that the assays developed are derived from the same components the participant’s samples will be. This is to comply with the FDA bioanalytical guidance.

Certain compounds have a high affinity for red blood cells and will have a large blood-to-plasma ratio. A high affinity for red blood cells can lead to overestimation of blood clearance if we can only analyse the plasma, so whole blood samples are necessary to avoid this. This partitioning data, alongside other parameters, will be used to inform physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models, that are key to us understanding how a drug will be absorbed, distributed, metabolised and excreted by a human body.

May Al Adwani

Certain compounds have a high affinity for red blood cells and will have a large blood-to-plasma ratio. A high affinity for red blood cells can lead to overestimation of blood clearance if we can only analyse the plasma, so whole blood samples are necessary to avoid this. This partitioning data, alongside other parameters, will be used to inform physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models, that are key to us understanding how a drug will be absorbed, distributed, metabolised and excreted by a human body.

It's clear that access to blood within CELT is not only helpful but absolutely necessary to progress these lifesaving long-acting medications to clinical trials and eventually manufacture. Within CELT, researchers are fortunate to have rapid, efficient, and carefully controlled access to fresh blood from healthy volunteers due to our on site capabilities and processes, and connection to the NCI.

There are many preventable diseases in the world with drugs to treat them, but adherence to demanding dosing regimens means they aren’t being cured. Prof. Neill Liptrott, Georgia and May’s work, along with the other research being overseen by CELT co-Directors Prof. Andrew Owen and Prof. Steve Rannard, is paramount to providing people with long-acting options for their medications and step us towards a world free of certain devastating but preventable and curable diseases.

How can you register to become a blood donor or book if you’re already registered?

Blood donation is critical and while the focus of this blog has been on the research and development perspective of using donated blood, the main use of blood donation to the NHS is to save and improve lives all over the country.

If you're interested in becoming a blood donor to the NHS, you have to be a registered donor which can be done online. Find out if you’re eligible to register and become a blood donor here.

Once you’re registered, or if you already are, there is a simple online system to book yourself in for your appointment. It will let you look by location and date to find the most convenient donation booking for you. Book your next donation here.

If you’re new to donation and would like to know more about what an appointment entails, the NHS have created a page to explain. Read more about what your blood donation experience will involve.