Context of the Square

Panel 4

The psychiatric hospital, known as the ‘Lunatic Asylum’, was erected on Ashton Street, a few streets to the north of AS in 1829 and remained in use until 1881 when it was converted for the use of University College Liverpool. Just below it on Brownlow Hill, Liverpool Parish workhouse was built between 1769-1772. The workhouse also housed what were known as ‘lunatic wards’ alongside other residential wards. To the south of AS the Women’s Penitentiary was sited in 1828. The mayor, bailiffs and burgesses of the Town of Liverpool granted a lease to the penitentiary of premises in Falkner St./Crabtree Lane, with the condition that they would be used solely for the rehabilitation of prostitutes. By 1921, the number of inmates had fallen to two and the Corporation closed the penitentiary. 48 tenements formed the Alms House on Cambridge Street, which gave accommodation to 96 almswomen. Each house provided two bedrooms and one living room. Residents used the parish church of St Catherine’s for baptisms as did the residents of 19-23 AS.

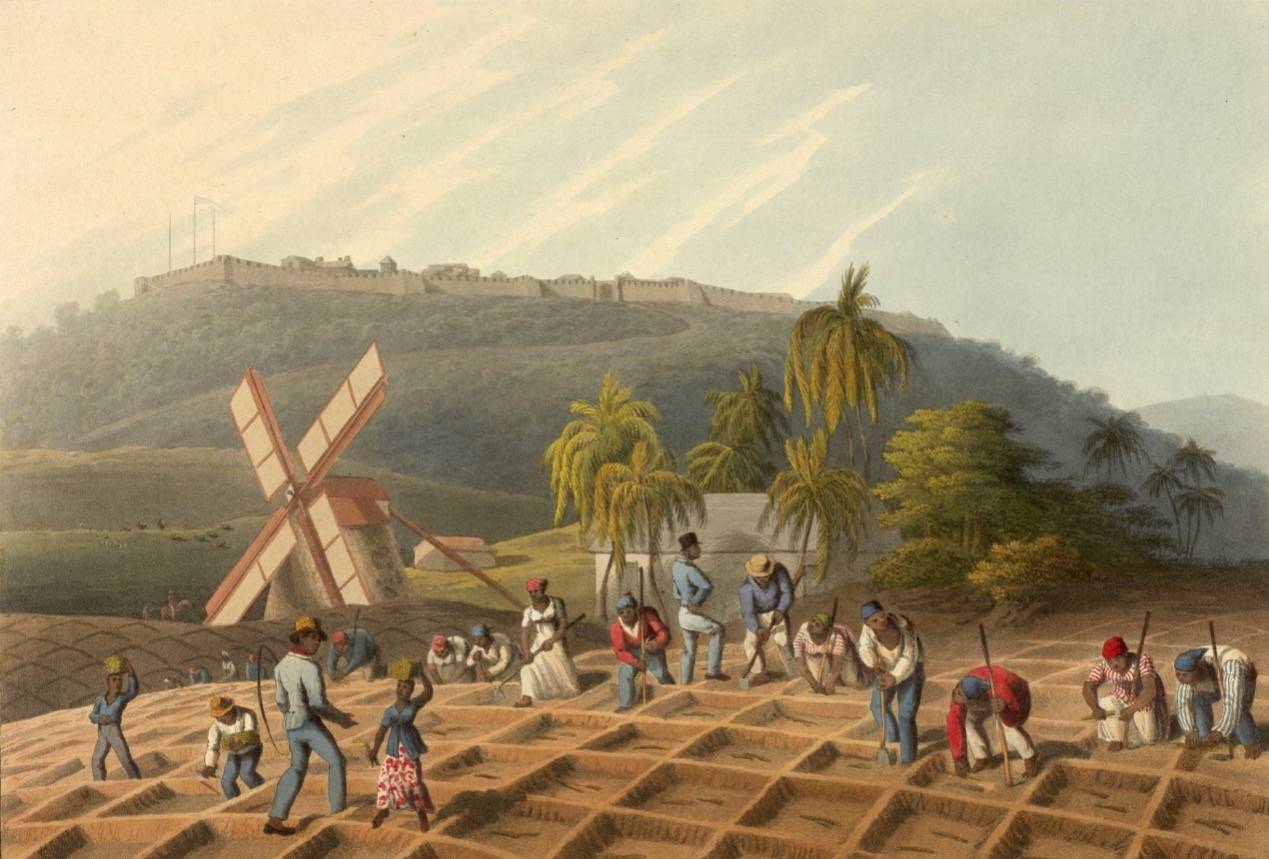

Enslaved people were imported to Jamaica as early as 1517 but when the British took the island from the Spanish in 1655, the potential for sugar profitability saw a dramatic increase in the use of slavery for plantations on the island. In 1662 there were approximately 400 enslaved people in Jamaica, which rose to 9000 eleven years later. Some of the sugar produced in the Caribbean was exported to non-British destinations but most of the sugar was shipped to Britain with 20% being re-exported to the Continent and Ireland.

Fig 4.1 Planting the sugar cane’ shows enslaved men, women and children working together in a field, from Ten Views of the Island of Antigua by William Clarke, 1813 (The British Library).

Link: National Museums Liverpool: Slavery in the Caribbean: https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/archaeologyofslavery/slavery-caribbean

References

Bartley, P. (2000) Prostitution: Prevention and Reform in England, 1860-1914. Routledge. 29-64.

Records of the Liverpool Female Penitentiary. The National Archives. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/1b252ab8-5bb2-4574-a10c-f512bc5aaa3a.

Peet, H. (1911) Liverpool's Alms Houses. Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Chester,62(1), 1-5

Baptisms at St Catherine Abercromby Square in the City of Liverpool, Baptisms recorded in the Register for 1831 – 1861. Parish Clerks for the County of Lancashire.https://www.lan-opc.org.uk/Liverpool/Liverpool-Central/stcatherine/baptisms_1831-1846.html

Historic England Research Records: Liverpool Lunatic Asylum. Historic England. https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=277f1253-fd67-4e00-b37f-e983c8b0298a&resourceID=19191

Murdoch, H. A. (2009). A Legacy of Trauma: Caribbean Slavery, Race, Class, and Contemporary Identity in “Abeng.” Research in African Literatures, 40(4), 65–88.

Richardson, D. (1987). The Slave Trade, Sugar, and British Economic Growth, 1748-1776. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 17(4), 739–769.