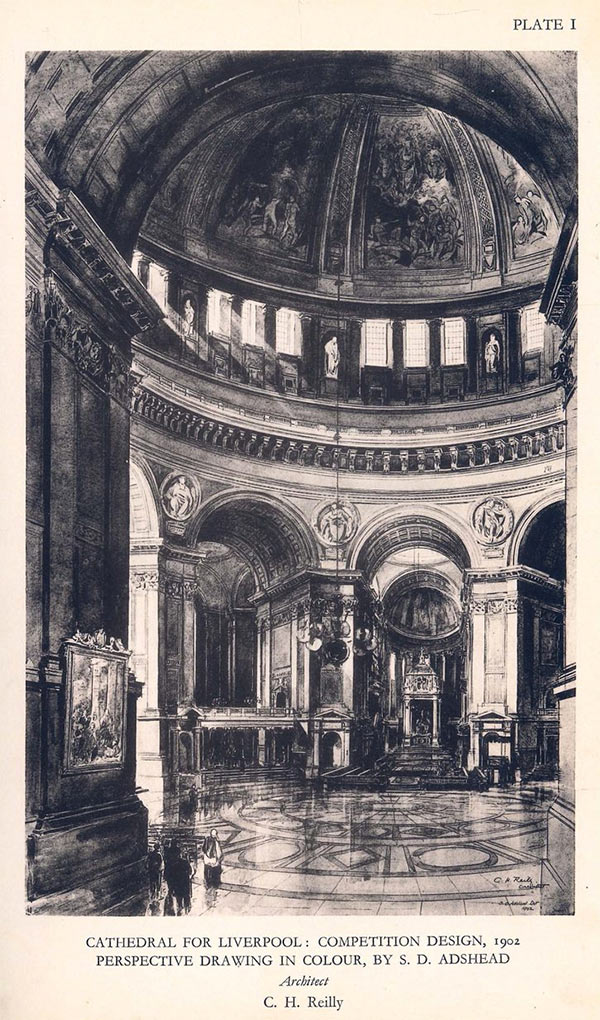

Professor Sir Charles Herbert Reilly (1874–1948), architect, teacher, town planner and journalist, was born in Stoke Newington, London, on 4 March 1874, the son of Charles T. Reilly (1844–1928), architect and surveyor to the Worshipful Company of Drapers. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, London, and Queens' College, Cambridge. After graduating in 1895 with a first in mechanical science, Reilly worked for two years as an unpaid draughtsman in his father's office, then moved to John Belcher's office as an ‘improver’. Here he came to know a number of leading young architects, including J. J. Joass, Stanley Adshead, E. A. Rickards, and H. V. Lanchester. In 1900 Reilly was appointed part-time Lecturer in Architectural Design at King's College, London, and joined in partnership with Stanley Peach to work on the design of electricity power stations. In 1902 he entered a classical design for the Liverpool Cathedral competition, earning a commendation from the assessors, and made an unsuccessful application for the Chair of Architecture at University College, London.

On 8 September 1904 Reilly married Dorothy Gladys (1884/5–1939), daughter of J. Jerram Pratt. That same year he was appointed Roscoe Professor of Architecture at Liverpool University. This conferred on him effective leadership of the university's young school of architecture, which he proceeded to build up with great verve. In 1906 was published the first of a series of volumes promulgating the work of the school, Portfolio of Measured Drawings. A second such volume of 1908 was succeeded by The Liverpool Architectural Sketch Book (1910, 1911, 1913, and 1920). Reilly's growing authority as an educator led to his becoming in 1906 the first chairman of the Royal Institute of British Architecture's Board of Architectural Education, a position he used to elevate formal and classical standards of architectural training against those who favoured a looser, less academic approach.

Reilly first visited America in 1909, which helped stimulate his interest in Beaux-Arts architecture and educational methods. As a result, with the backing of W. H. Lever (Lord Leverhulme), with whom he had developed a close working relationship, he helped establish at Liverpool University the Department of Civic Design, effectively the first place in Britain where town planning and architecture were taught as integrally related subjects. With the expansion of the school Reilly persuaded Lever to fund a new building. In 1914 he produced designs, but the outbreak of war meant they were not executed and it was not until 1933 that the Leverhulme Building, designed by Reilly in collaboration with his former students Lionel Budden and J. E. Marshall, was finally opened. Earlier Reilly had built the university's students' union (1909–14). Though not primarily remembered as a designer, he could on occasion be impressive, as in the austere church of St Barnabas Shacklewell, London (1909). He also designed one of the many groups of cottages for Leverhulme's model village of Port Sunlight (1906).

Reilly's breadth of interests involved him in 1911 in a campaign to establish the Liverpool Repertory Theatre, of which he was board member (and at one time chairman) until his retirement in 1933. Also in 1911, he was appointed a member of the faculty of architecture at the British School at Rome.

In 1913 Reilly was appointed consulting editor to the Builders' Journal. After the war his journalistic output increased and he contributed to the Manchester Guardian and Liverpool Post, and reviewed for the Architects' Journal and Architectural Review. Reilly was appointed architectural editor at Country Life in 1921, the year in which he published Some Liverpool Streets and Buildings in 1921 - a collection of articles on the city's architectural stock. In the following year he produced a similar volume on Manchester's architecture, together with two other books, McKim, Mead and White and Some Architectural Problems of Today. Other books included Representative British Architects of the Present Day (1931), The Theory and Practice of Architecture (1932), his autobiography, Scaffolding in the Sky (1938), and Architecture as a Communal Art (1946).

Reilly spent the First World War as an inspector of munitions. In 1919 he again visited America and Canada and subsequently sat as a jury member for the Canadian war memorials competition. He designed the Accrington war memorial, Lancashire (1920), and the Durham war memorial (1928), and acted as assessor for the Liverpool cenotaph competition (1926). He travelled in India with Lutyens in 1927–8. In 1923–4 Reilly was appointed co-architect with Thomas Hastings to design a large Beaux-Arts apartment block: Devonshire House, Piccadilly, London. In 1931 he was successful, with others, in his campaign for the passing of the Architects' Registration Act.

In 1933, with his health failing, Reilly retired to Brighton, but he continued to work on his journalism and acted as consultant architect with William Crabtree (a former student) on the Peter Jones store, Sloane Square, London (1935–9). The design was strikingly modern and much praised. By the late 1930s Reilly had become an enthusiastic advocate for modernism and in 1944 he was proposed as an honorary member of the Modern Architectural Research Group (MARS), by his former student Maxwell Fry.

Cathedral for Liverpool competition design, 1902. Published in the Book of the Liverpool School of Architecture, The University Press of Liverpool and Hodder and Stoughton Ltd London, 1932. Plate I.

In his later career Reilly was involved with town planning issues, writing numerous articles about rebuilding towns and cities. His criticism of the 'Academy Plan' for London brought him into conflict with Lutyens and other former friends. Reilly's planning theories were brought together by Lawrence Wolfe in The Reilly Plan: a New Way of Life. Here a series of ‘Reilly greens’ is described, around which communal housing schemes were to be arranged. The idea was unsuccessful when first proposed for Woodchurch, Birkenhead; the town was eventually designed by Reilly's former student Herbert Rowse. Modified versions of the plan were implemented in Bilston, Staffordshire, and Dudley, Worcestershire. Reilly in collaboration with Naim Aslan published The Outline Plan for the County Borough of Birkenhead (1947).

In an obituary written for his former professor William (Lord) Holford described Reilly as 'an international figure, not only by reputation but by the building up of personal contacts'. His circle of friends encompassed many fields from the arts to politics. Augustus John painted his portrait in 1932, and the fashionable Liverpool photographer E. Chambre Hardman photographed Reilly with hat and ivory-topped cane—which, Holford recalls, he used to knock on the doors of 'peers and poets and the poor'. Maxwell Fry described him as looking like 'a cherub … a laughing, naughty cherub about to direct an arrow where least expected … His fleshy childlike features … in thoughtful repose, his cupid's mouth slightly pursed … wearing a broadbrimmed black hat … from which stray a few white hairs'. Reilly was an enthusiastic joiner and member of clubs, including the Athenaeum, London, and the University and Sandon clubs, Liverpool, as well as being a sponsor of the ‘1917 Club’, London, founded by Ramsay MacDonald to promote world peace. Indeed, Reilly's lifelong socialism informed much of his personal and professional life. Reilly was a charismatic figure and an inspirational teacher, who turned the Liverpool School of Architecture into one of the most famous schools in the world during the inter-war years.

Among Reilly's many honours were an honorary LLD from Liverpool University (1934), the Royal Gold Medal for architecture (1943), and a knighthood (1944). He died on 2 February 1948 at the Gordon Hospital, Westminster, London, his wife having predeceased him in 1939, and he was cremated four days later at Golders Green. He had four children, of whom two - a son and a daughter - survived him. His son, Paul Reilly, Baron Reilly (1912–1990), was closely associated with the Design Council.

The Charles Reilly Medal is awarded in the MArch each year.

Further reading

Peter Richmond, Marketing Modernisms: The Architecture and Influence of Charles Reilly, Liverpool University Press, 2001.

Joseph Sharples (ed.), Charles Reilly and the Liverpool School of Architecture 1904-1933, Liverpool University Press, 1996.

Christopher Crouch, Design Culture in Liverpool: The Origins of the Liverpool School of Architecture, Liverpool University Press, 2002.

Charles Reilly, Scaffolding in the Sky: A semi-architectural autobiography, Routledge, London, 1938.

Back to: School of Architecture