1924 Women at the LSA: Norah Roberts née Dunphy (1903-1966) and Thelma Edwards née Silcock (1903-1996)

In 2024 we celebrated the centenary of our RIBA validation with special alumni events and lectures from RIBA Gold Medallist Professor Lesley Lokko OBE and alumnus Professor Robert Nicholls. Emma Curtin looks back to the school in 1924, and considers the experiences of two young women architecture students who were approaching the end of their training.

Centenary events invite us to cast our minds back, in this case to 1924, the year of the first RIBA visiting board that granted Liverpool School of Architecture (LSA) graduates full exemption from RIBA professional exams.

I am curious about what it was like here then, for Norah Roberts née Dunphy (1903-1966) and Thelma Edwards née Silcock (1903-1996), two young women architecture students who were among some of the first women in the country to attend university, let alone study architecture.

Universal suffrage was still a few years away (1928). The impact of WW1 must have been present with many students having seen active service. The legacy of women’s work during the war had changed attitudes about what women could do, and the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act had put into law the right to gain a degree and enter the professions. There was a growing interest in architecture as a career for women. Contemporary publications periodically promoted the idea, often linking the notions of women’s knowledge of the home, and their talents in the decorative arts, with their suitability for the profession. An attitude evidently found at the Architectural Association (AA), where women students complained of being restricted in their studies and projects. Elizabeth Scott was just graduating from the AA and would go on to win the prestigious Stratford Shakespeare Theatre competition a few years later. Meanwhile in Liverpool, there is evidence that women were already designing ambitious projects during their studies.

Norah Dunphy – Thesis Project A Hydropathic Establishment – By Courtesy of the University of Liverpool Library

The Liverpool School of Architecture is one of the oldest in the country and was the first to offer a full-time professional course, its undergraduate degree recognised by the RIBA since 1895. Already by the 1920s the school had a strong reputation. Admitting students from both the local area and around the world, the school’s far-reaching influence on 20th century architecture is well established, and new research is beginning to re-consider the school’s history though an intersectional lens. Professor Charles Reilly, Roscoe Chair in Architecture 1904-1933, later a RIBA Gold Medallist, was committed to the development of architectural education. Reilly apparently supported women’s education and there was generally a progressive attitude to women’s education in the city of Liverpool underpinned with resources from benefactors such as the women of the Holt Family. The University had admitted women from its inception and had accommodated women with common rooms and Halls of Residence. The School of Applied Arts had also admitted women students from the 19th century.

In the UK, women attaining degrees in increasing numbers in the 1920s were typically from middle class backgrounds, for example their fathers were traders or in the professions, they were not poor, but they expected to put their degrees to use in employment after graduating. Both women architecture students could be seen to fit this mould. Norah Dunphy grew up in Llandudno where her family ran a small chain of Grocers shops and Thelma Silcock had lived in Huyton closer to Liverpool, her father was a Tobacco Factory Manager.

During their studies the women may have lived in digs or even women’s halls of residence or perhaps Thelma would have commuted from her family home in Huyton, by train.

Following her architecture degree Norah continued her studies at the new School of Civic Design gaining a 1st class certificate in Civic Design. Her thesis project was for Hydropathic Establishment.

Of course, universities were famously also a good place to find a husband, particularly for this generation in the post war period when the term surplus women was used to describe the imbalance in gender populations highlighted by the 1921 census. Thelma did meet her husband at the LSA but she also proved to be an exceptionally talented architecture student, winning school prizes and in 1925, the most distinguished national student prize, the RIBA silver medal. The third year in a row that it was won by a female student. Thelma was also already working with her fiancé on housing and ecclesiastical projects in North Wales and Cheshire, and they had formed the successful practice which became W.B. Edwards Architects.

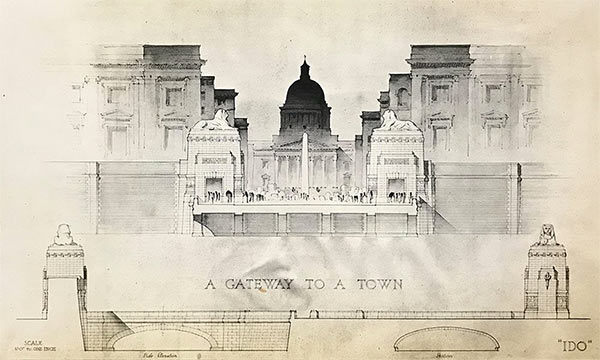

A Gateway to a Town - Drawings for the Rome Scholarship 1925 by Thelma Silcock. By Courtesy of the University of Liverpool Library

Once I’d established the women’s success at the LSA I was curious about what they did next and whether they were able to, or even interested in forging careers in architecture. As with any hidden history it is difficult to unpick a story with limited information but in a way that is where it gets more interesting. They were exceptional, and celebrated in the press as pioneers at the launching moment of their careers: Thelma winning the Silver Medal and Norah credited as the 1st woman “in the empire” to attain the BArch and to work in Town Planning. It appears both went on to have successful careers but not successful in the way that has traditionally been necessary to become part of an official celebrated history, for example like James Stirling or Reilly himself. However, as we reexamine our history the value of these stories becomes clear, illustrating a wider social history of women’s experiences of architecture in the 20th century and recognising the impact women have long had on the built environment.

Norah had a successful career in Town Planning for close to 20 years. Following her marriage and the birth of her daughter Ann in 1943 she worked part time as a lecturer teaching town planning to architecture students, and she also played a significant voluntary role with the Scouts and Cubs.

Norah’s Drawings - County Borough of Tynemouth, Houses to Accommodate 248 Families, Ridges Estate, North Shields. By Courtesy of the University of Liverpool Library

Some aspects of Thelma’s story are harder to follow, and she did not have children. We can work out her movements by following her husband’s more well documented career and using public records. Her contribution to their practice is to some extent erased from memory by the practice name W.B. Edwards and partners. But there is evidence to suggest she was a partner, and we know she certainly had the necessary skills and tenacity. She is remembered by a family friend as formidable, (as well as generous), and her design talent is a matter of public record. Historian Elizabeth Darling writing about 20th century husband and wife architectural partnerships uses the example of Herzog & de Meuron to remind us that we tend to accept shared authorship and value the contributions of both parties in all male collaborations.

W.B. Edwards & Partners became an important practice in the North East of England with significant, published commissions in the mid 20th century including a women’s hall of residence for Newcastle College of Durham University, where Thelma’s husband Wilfrid was head of the architecture school. The couple retired to a house they had built for themselves in Wales and sadly Wilfrid died soon after. Thelma lived there for the rest of her life and was involved in local architectural conservation campaigns in her retirement.

Both women were modest, friends and family were not all aware of their remarkable achievements and whilst we have some of Norah’s papers, Thelma’s are lost, leaving us to piece together a picture from public records and ad hoc memories of younger friends and family.

Its almost 100 years since both women set out to use their degrees and begin to establish successful careers in the built environment, and since Thelma won the RIBA Silver Medal. Strikingly the ways in which they balanced careers, and their home lives are not dissimilar to the ways that women balance careers in architecture a century later. Better understanding women’s sometimes invisible experiences in architectural education and practice in the 20th century illuminates the influence women have had on the built environment. It invites us to revisit dominant historical narratives which sometimes underestimate the contributions of a wider team. Recognising the collaborative nature of design, and exploring women’s varied working and career patterns, including interactions with family life, brings new nuance to familiar architectural histories and places. This social history, challenges some of our gendered notions of 20th century architectural practice, without denying the underrepresentation of women, and the challenges they faced to be able to work in architecture. It may also have value as a missing piece of background for contemporary women working in architecture.

Whilst women students were winning the RIBA silver medal in the 1920s, it was close to 90 years before an individual woman, Zaha Hadid, won the gold medal. Patricia Hopkins,’ was the first woman to be awarded the Gold Medal, shared with her husband in 1994. Famously photoshopped out of a picture of 20th Century Architects, she has quite literally been erased at times, neatly illustrating both how women’s value in a husband-and-wife partnership can go unrecognised, and the sorts of challenges faced in unpicking hidden histories.

Further Reading

Darling, Elizabeth, and Lynne Walker. n.d. AA Women in Architecture, 1917-2017

Dunne, Jack, and Peter Richmond. 2008. The World in One School : The History and Influence of the Liverpool School of Architecture 1894-2008. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Dyhouse, Carol. 1995. No Distinction of Sex? UCL Press#

Robinson, Jane. 2020. Ladies Can’t Climb Ladders. Random House.

Sharples, Joseph, Alan Powers, and Michael Shippobottom. 1996. Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture, 1904-1933.

Waite, Richard. 2014. BBC Slammed for “Bias” after Patty Hopkins Is Sidelined in TV Show. Edited by Laura Mark.The Architect’s Journal, March.