In this ACE and Creativity series blog post, Skylar Masuda discusses Sappho's poetry, and walks us through an exhibit inspired by Sappho.

Sappho. Fragment 31, from If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, translated by Anne Carson

thin / fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all

Sappho’s Fragment 31 feels like an assault on the senses, forcing the reader into the body of the poet as she sees the person she loves with another. Her poetry pulls readers in with evocative sensory details, giving us a window to life, love, and loss in ancient Lesbos.

As one of the earliest historical touchstones for imagining queer identities, the actual content of Sappho’s work is often overshadowed by discussions about her. Because where is she? Though rich with detail, her surviving poetry gives few basic life details. As a student studying Sappho’s work in my final year at the Claremont Colleges, I found this lack of information destabilizing. When I looked at her poetry, instead of finding answers I found:

greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

Expecting to find corporeal descriptions, a physical anchor for her love stories, I was

instead offered a wealth of incorporeal details. In her 2016 article “Re-Queering Sappho,” Professor Ella Hasselswert expressed a similar journey:

Rather than identification with an imagined biography, I find in Sappho an ethical, aesthetic,

and affective complex that is meaningfully familiar.

She notes that this “affective complex” denies misogynistic conventions of property,

ownership, and physicality. I had the honour of attending Professor Hasselswert’s 2023 Harry Carroll Memorial Lecture, which built upon these ideas and explored modern artistic responses to Sappho’s work. Emphasizing Sappho’s resistance to figuration and positivism, Hasselswert explored Sappho’s work as an inherently queer realm of abstraction, one that offers new and generative ways of imagining antiquity.

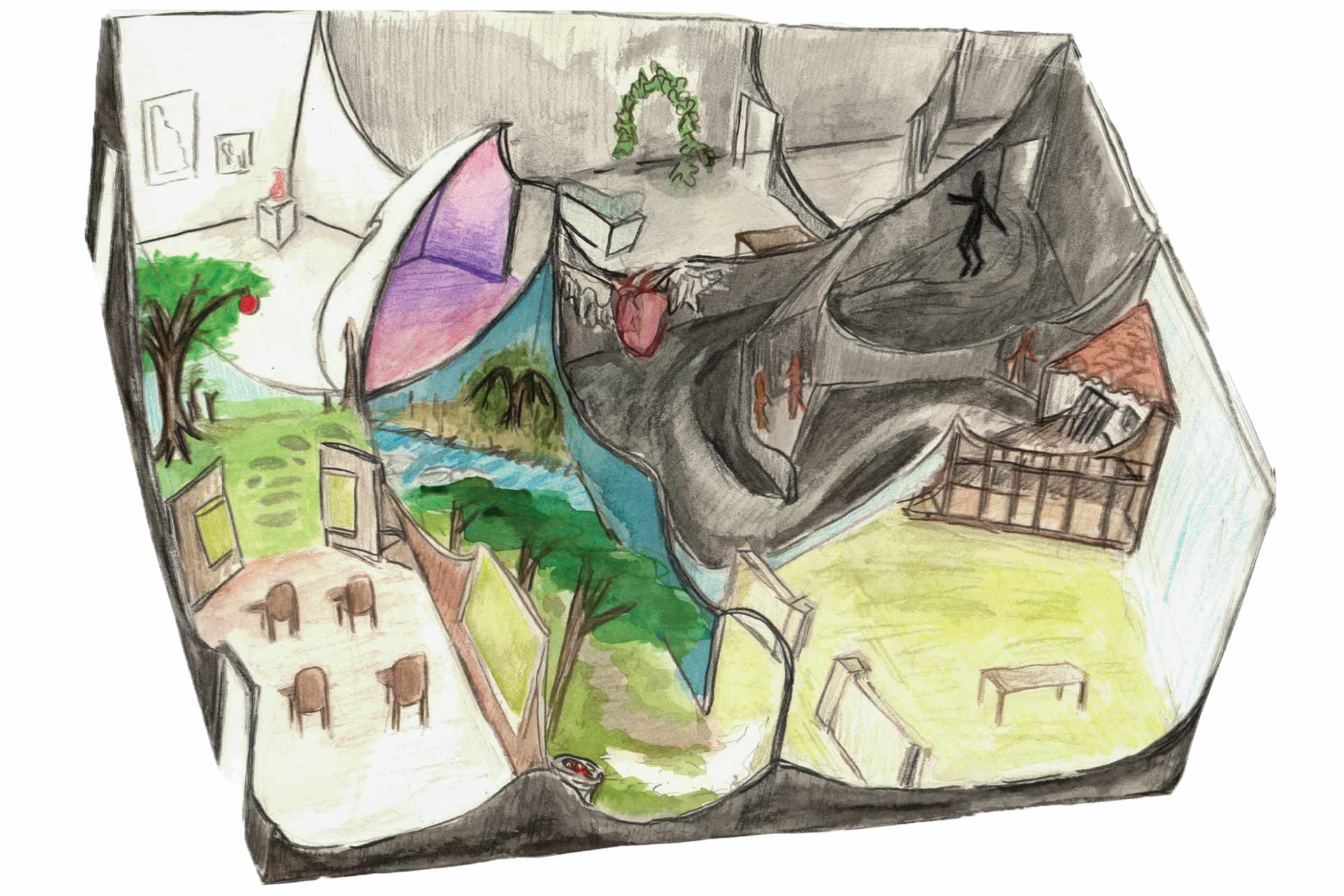

I began to imagine an exhibit that could do what Sappho’s poetry does: immerse us in sensory experience.

The exhibit

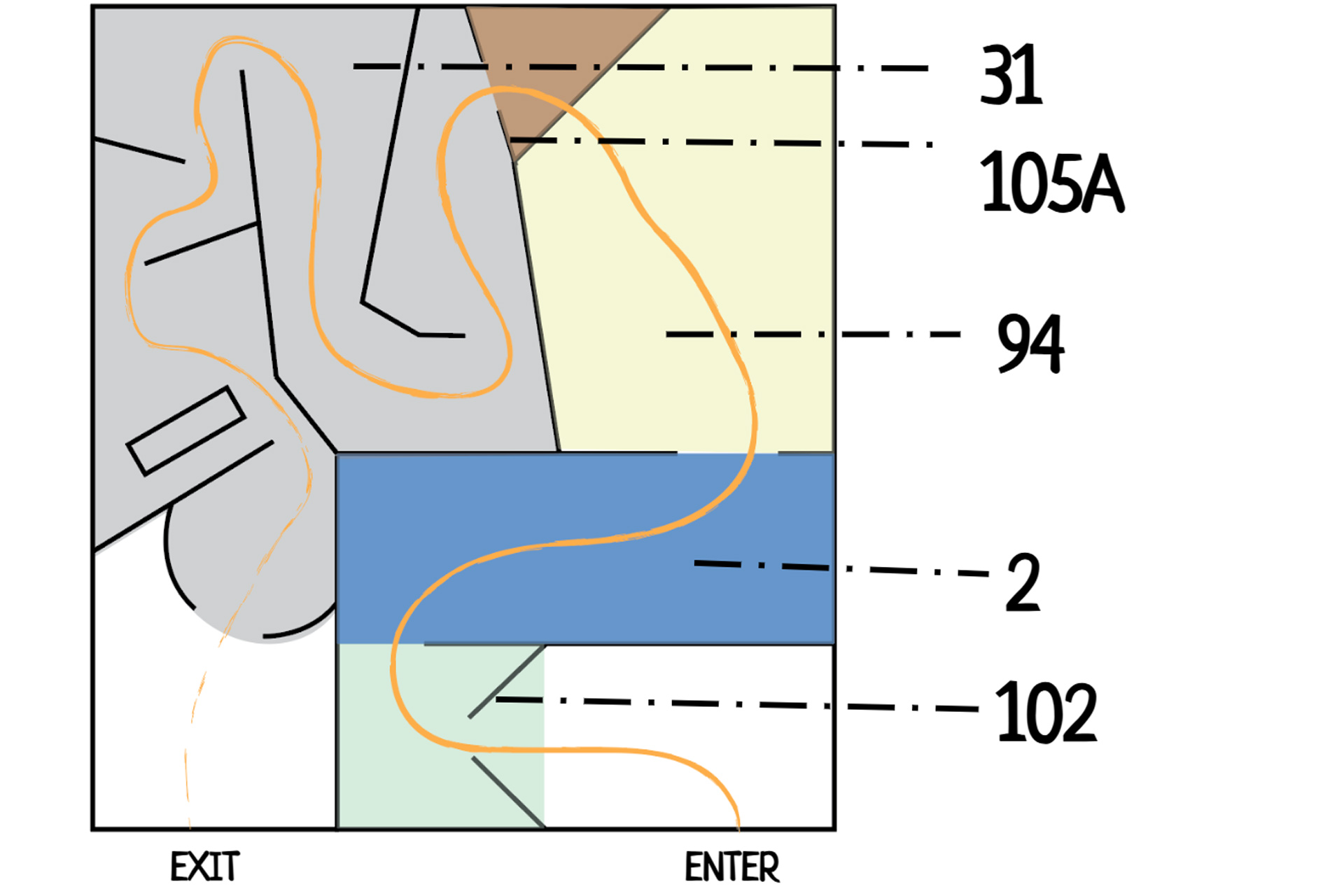

Visitors begin by walking into a small classroom with linoleum flooring and scuffed wooden desks, a reminder of time spent learning about ancient Greece in school. On one wall is a chalkboard with a simplified timeline of ancient Greek civilizations, with Sappho’s name circled in the early 7th century B.C.E. As visitors wander through the classroom they see another whiteboard with ancient Greek writing. This poem will be unreadable to most visitors:

οἶον τὸ γλυκύμαλον ἐρεύθεται ἄκρῳ ἐπ’ ὔσδῳ,

ἄκρον ἐπ’ ἀκροτάτῳ, λελάθοντο δὲ μαλοδρόπηες·

οὐ μὰν ἐκλελάθοντ’, ἀλλ’ οὐκ ἐδύναντ’ ἐπίκεσθαι.

The wall splits open, cracking the poem in two and revealing an orchard. Through trompe l'oeil wall paintings, fabricated set pieces, and projection techniques, visitors are welcomed inside the poem, smelling sweet fruit and standing underneath the tree. Projected on the wall in front of them is the translation of Sappho Fragment 105A:

as the sweetapple reddens on a high branch

high on the highest branch and the applepickers forgot—

no, not forgot: were unable to reach

In the next room, they traverse a river on stepping stones until they reach a meadow. The room is darkened and small twinkling stars dot the sky. Visitors hear the running water and smell sweet flowers and gentle smoke on the light breeze. Sharp eyes may spot horse hoofprints in the soft dirt pathway, signs of life and movement. They find a still-smoking altar, a recreation of Fragment 2.

The following rooms invite visitors to make flower garlands (Fragment 94), and show

them a massive replica of an ancient Greek loom, complete with an unfinished weaving project and a suspiciously empty stool (Fragment 102). Entering a darkened mazelike section they find art based on the intense descriptions of Fragment 31, including a large sculpture of an anatomical heart suspended on bird wings, and an illuminated skeleton gently flickering with neon lights.

Hearing heartbeats and buzzing, they walk through sections that seem to change temperature. In one room, they are asked to help complete a paper mache sarcophagus by writing on rice paper and glueing it to the collaborative art piece. Each piece of paper responds to the prompt, “What does love feel like?”

The final rooms feature an exhibition space that hosts rotating art from contemporary female and queer artists created in response to Sappho’s work.

Sappho’s denial of physicality demands a reexamination of object-focused curatorial

practices. An exhibit that delivers the same evocative, abstract, and multisensory experiences as her work serves as grounds to explore new, and potentially more generative museum experiences, reminding us what might be gained from a creative alternative.

Illustration of exhibit: