PhD Student Pascale, discusses a number of nationalist and traditionalist sentiments on Youtube videos about Romulus, Remus, and the founding of Rome in this month's ACE & Creativity blog post

In an influential essay for Eidolon, Rebecca Futo Kennedy (2017) argues that many nationalists, traditionalists, and those on the alt-right are drawn to ancient Greece and Rome because they believe it was a simple time, before the perceived “modern” perils of gender equality and the acceptance of immigrants. In our own research on YouTube videos and comments as part of the Rome From the Ground Up project, we’ve also seen a number of nationalist and traditionalist sentiments on videos about Romulus, Remus, and the founding of Rome. Although the Roman empire may seem like a more obvious site of comparison to the modern world, the Romulus and Remus myth is of great interest in conversations about national identity and tradition. Much of the admiration of Rome by the online alt-right seems to be for Imperial Rome, with its territorial expansion and military power over “barbarian” others, but Romulus and Remus come long before the Roman Empire, or even the Republic.

The national admiration for the myth

The nationalist admiration for the myth might then be because of Romulus’ role as the founder of Rome.In Livy’s narrative of the myth, which is the only ancient source we’ve found directly cited in a comment from our dataset, Romulus is situated as an “exemplary” figure that should be imitated and as “the founder of Roman power” (Stem 2007, p. 440). However, the version of Romulus that we see in these videos is quite partial: the videos focus on his exposure as a baby, the death of Remus, and occasionally the Sabine women, ignoring many other aspects of his career that were both important and exemplary to Romans such as his establishment of the Asylum for immigrants and runaways.

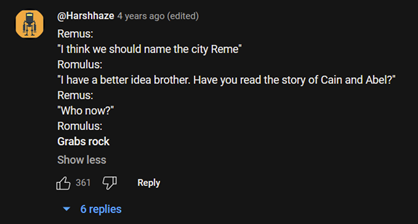

However, it’s not just Romulus’ role as the founder of Rome that might appeal to a nationalist commenter, but elements of the myth itself like the fratricide, or the Rape of the Sabines. In this myth, and other city foundation myths like that of the biblical Cain and Abel, and in the comments in our dataset, fratricide is often linked to city-founding:

Comparisons between the Cain and Abel myth and the Romulus and Remus myth appear often, with the only explicit comparisons drawn between the two myths being their shared elements of fratricide and city-founding. One of the reasons that scholars have linked murder to city-founding is an element of divine sacrifice. Bruce Lincoln (1975) locates Remus’ murder by Romulus as sacrificial and necessary for the foundation of the city. One comment author in our dataset makes this connection to sacrifice, explaining Remus’ death as “an explanation of a gruesome sacrificial tradition to protect the sanctity of city walls.”

“Brotherhood emerges as the image of the ideal national community"

Angelina Ilieva (2005) takes up the idea of this cleansing sacrifice in reference to several national literary texts from the Slavic world: she writes that “brotherhood emerges as the image of the ideal national community, whereas the necessity to cleanse the national self from the invasion of a demonic other takes the form of a fraternal sacrifice” (p. ii-iii). Ilieva uses Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome as a parallel for these works dealing with fratricide and the literal or metaphorical foundation of a nation or national identity, because of the way the fraternal relationship symbolises dualism and equality. She cites T.P. Wiseman’s (1995) assertion that the founder of Rome only became a set of twins in the fourth century BCE, to provide mythical context for the power sharing between patricians and plebeians. In the context of modern national texts, the fratricide works to evoke a shared sense of loss and victimhood, violently severing the image of the nation as brotherhood. The memory of this historical trauma then serves to invoke a sense of longing for the imagined national brotherhood of the past, both within the narratives and the texts and for the reader. The fratricide in these texts is the direct result of a foreign invader, upsetting the brotherly relationship, a concept which maps easily to contemporary nationalist sentiments on immigration; the longing for the past is reminiscent of the traditionalist desire to return to not only a simpler and happier time, but one where the nation is powerful and undivided.

Modern far-right nationalism hinges upon the idea of a privileged in-group and a newcomer who is usurping those privileges. The version of the myth of Romulus and Remus that we see most frequently on YouTube is the version in which Remus jumps over Romulus’ wall, recalling debates across Europe and North America regarding migration. These videos casually memorialise fratricide, which is not how Roman authors approached Romulus and Remus; we know that authors who had experienced civil war, like Horace and Ovid, portrayed a more traumatic account of Remus’ death. Focusing on only limited aspects of Romulus’ biography to serve an explicit agenda aligns with Ilieva’s understanding of these texts, despite their differences in time and place. It is important for classicists to realise that even seemingly benign stories about Rome can be weaponized in internet discourse.

Bibliography

CSMFHT (2023) ‘Why Rome? Classics & Alt Right: Part 1’, CSMFHT Writes, 20 August. Available at: https://csmfht.substack.com/p/why-rome-classics-and-alt-right-part (Accessed: 4 January 2024).

Ilieva, A.E. (2005) Romulus’s nations: Myths of brotherhood and fratricide in Russian and south Slavic national narratives. Ph.D. Northwestern University. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/305404176/abstract/5554EBC61913417BPQ/1 (Accessed: 10 July 2023).

Kennedy, R.F. (2017) ‘We Condone It by Our Silence’, EIDOLON, 11 May. Available at: https://eidolon.pub/we-condone-it-by-our-silence-bea76fb59b21 (Accessed: 4 January 2024).

Lincoln, B. (1975) ‘The Indo-European Myth of Creation’, History of Religions, 15(2), pp. 121–145.

Stem, R. (2007) ‘The Exemplary Lessons of Livy’s Romulus’, Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), 137(2), pp. 435–471.

Wiseman, T.P. (1995) Remus: a Roman myth. Cambridge ; Cambridge University Press.