These pages concern the tidal Dee estuary that is located on the border of North Wales and England. There are also rivers called Dee in Scotland (at Kirkcudbright and at Aberdeen).

The natural head of navigation of the Dee is Chester. Here there was a bridge over the river and an important town. Chester was a port from Roman times on. The original port anchorage was where the Rodee (racecourse) is now - close, as you would expect, to Water Gate. Even in Roman times, an "outport" was maintained - at Meols on the north Wirral shore. By 1855, the port of Chester was alongside the river at Crane Wharf with the Dee Branch canal basin acting as a dock for barges and flats: see sketch. As the Dee gradually silted up, ports such as Parkgate became more important. They could be reached, given favourable winds, on one tide from the open sea and provided reasonable shelter.

Exports from Chester included cheese, and linen imports from Ireland were significant. The nearby Fflint area provided lead ore which was carried as ballast in sailing vessels. Coal was available from Ness (colliery from 1759, near Parkgate) and also, later, from mines on the Welsh side of the estuary. There was a significant trade carrying coal to Ireland from Point of Ayr Colliery.

The Dee provided a convenient base for military expeditions to

Ireland.

From 1600, substantial numbers of troops, provisions and

equipment were sent to Ireland.

For example, in the 9 years war, Sir Henry Docwra and 3000 men,

200 horse, 3 canons, were shipped from "near Helbree" on 25 April 1600

and after regrouping at Carrickfergus, they landed on 14th May at Lough

Foyle and set up a garrison at Derry. More detail.

On 16 November 1643, about 2,500 troops (4 regiments of foot

and one of horse) landed at

Mostyn from Ireland to support the Royalist cause in the Civil War; and

another contingent landed at Neston on 6 December..

The Cromwellian invasion of Ireland of 1649-1650 was initially

mounted from Milford Haven, but a huge number of sailing vessels were

needed to transport troops and their equipment. There were complaints

from inhabitants of the Wirral about the rapacious conduct of troops

waiting to be transported from the Parkgate area.

In April 1690 King William III (William of Orange) left Hoylake [then a

deep water anchorage - the Hyle Lake] with a force of 10,000 troops for

Ireland. The King, himself, stayed at Gayton Manor (near Heswall) while

waiting for suitable weather to depart from Hoylake. His departure from

Hoylake is commemorated by the "King's Gap" - now an area of Hoylake.

There were earlier royal connections too: Richard II was trapped in

1399 by Henry Bolingbroke (Later Henry IV) at Fflint Castle (built

1277-84 by Edward I) - as dramatised by Shakespeare.

Much earlier, in 973, 6 regional kings pledged allegiance to King

Edgar at Chester. This story was later embellished as 8 kings rowing

Edgar up the river Dee in the Royal Barge - and Edgar's Field is a park

at the south end of the old Dee bridge commemorating this.

The channel in the Dee Estuary has changed considerably over the centuries. The sand (and mud) banks have shifted and built up too. The deep channel used to run near the Wirral coast with ports at Shotwick, Neston, Parkgate, Heswall and Dawpool. Parkgate was a busy port with regular services to Ireland and a ferry crossing to Bagillt. After the new cut was made in 1737 to straighten and canalise the Dee from just below Chester to near Fflint, the deep channel moved over to the Welsh side with quays and ports at Sandycroft, Queensferry, Connahs Quay, Shotton, Fflint, Bagillt, Greenfield, Mostyn and Talacre.

See here for some historic images of shipping in the Dee Estuary.

See here for some old charts from 1697, 1771, 1800, 1840 and from 1850.

See here for some old sailing directions to the Dee Estuary: from 1840 and 1870.

A snapshot of shipping volumes in the Dee Estuary in the 1880s, and 1891 Census Return of shipping in the Dee.

Early steam vessels in the Dee.

The channel is still changing: so wrecks get covered and old wrecks get exposed. Here I list the best known wrecks.

Wrecks (especially those with known position) are presented starting

from the SE (upriver) working outwards.

Back to top

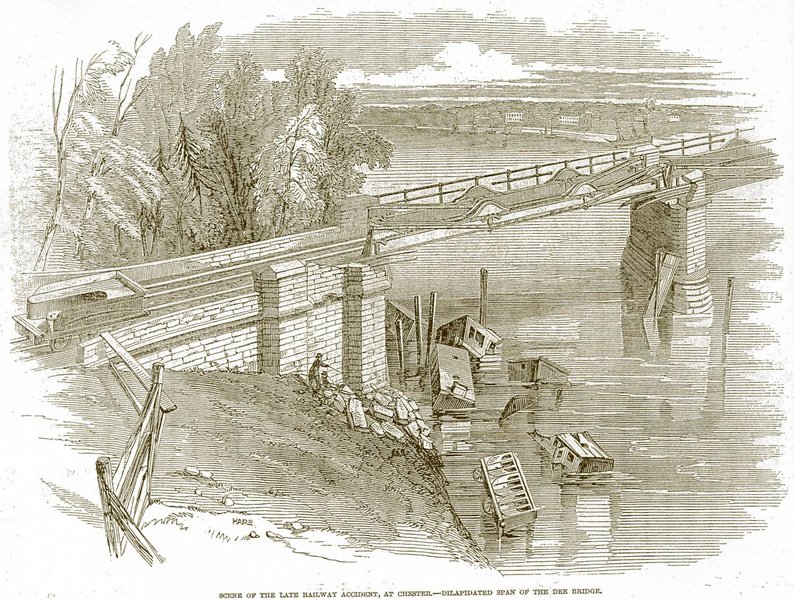

The first "wreck" is actually not a ship at all - rather a railway accident that precipitated coaches and people into the tidal river Dee. The Rail bridge near Chester (just downriver from the Roodee) was opened in 1846. It failed on 24 May 1847 as a passenger train was crossing and some coaches fell (with iron girders from the bridge) into the river Dee. Of the 24 people aboard, there were 5 fatalities.

The bridge had been designed by Robert Stephenson, the son of George Stephenson, for the accommodation of the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway (Shrewsbury to Chester Line). It was built using cast iron girders produced by the Horseley Ironworks, each of which was made of three large castings dovetailed together and bolted to a raised reinforcing piece. Each girder was strengthened by wrought iron bars along the length. It was finished in September 1846, and opened for local traffic after approval by the first Railway Inspector, General Charles Pasley.

On 24 May 1847, the carriages of a local passenger train from Chester to Ruabon, going at about 30 miles per hour, fell through one of the 98 ft cast-iron spans of the bridge into the river. The engine and its tender got across but the coaches fell with the girders into the river Dee. The engine was actually able to proceed (without tender) and so warn other approaching trains. The accident resulted in five deaths (three passengers, the train guard and the locomotive fireman) and nine serious injuries.

Image of the aftermath of the accident (showing derailed tender and

carriages in the river):

Image of Dee railway bridge a few years later(at far upper left).

Fuller Reports into the Accident

Robert Stephenson was accused at a local inquest of negligence. Although strong in compression, cast iron was known to be brittle in tension or bending, yet the bridge deck was covered with track ballast on the day of the accident, to prevent the oak beams supporting the track from catching fire. Stephenson took that precaution because of a recent fire on the Great Western Railway at Hanwell, in which a bridge designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel had caught fire and collapsed. The Dee bridge disaster was a traumatic event which led to the demise of cast iron beam bridges reinforced by wrought iron tie bars.

The bridge was fully rebuilt in 1870-1 using bricks and wrought iron.

Bridge in 2014.

Back to top

Before the Queensferry road bridge (Blue, opening, built in 1897 and

rebuilt in 1927) and nearby opening rail bridge (built 1889), the first

bridge over the Dee was at Chester. Ferry services were available at

several locations. After the new cut was made in 1737, a ferry service (free)

was established at Lower Ferry (later called King's Ferry and then

Queen's Ferry) - located exactly where the blue Queensferry Bridge is

now.

Aston Quay (referred to in the report below as Aston Stage)

was located on the Fflint side of the river just up-river of the

location of the A55 road bridge.

Here I first record one of the largest losses of life associated

with these ferry services:

It is with feelings of extreme regret; we [contemporary newspaper North Wales Gazette] have to record a most frightful accident, by which eleven human beings have been deprived of life, and which occurred on Monday night week [29 June 1824], at the Lower Ferry, about 6 miles down the Dee from Chester. On the above day, a great number of people, chiefly from the Flintshire side, had collected together, at the Ferry-house, which is also an ale-house, kept by Arthur Gregory, to witness a sort of rowing matches, and after the close of the day had retired to the house, to enjoy themselves with good cheer and a dance. Soon after ten o'clock, some of the company, who had to cross the river, were on the move and the moment was extremely unpropitious. The first of the flood, or what is commonly called the head of the tide, passed up the river at this place about half-past ten, when the ferry-boat for the first time crossed full of women.

Our informant, who was at the landing-place on the opposite side, saw them make the shore with the greatest difficulty. The boat returned, and brought over another load, who were in the greatest danger, the boat being so full as not to allow the passengers to sit down. The young men who managed the boat then said, they would not bring any more over till high water. However, at about twenty minutes before that, they again attempted - but having advanced nearly to the middle of the river, the obvious danger arising from the impetuosity of the current, determined the young men who had the management of the boat, to return. A contest now commenced which terminated in the fatal catastrophe; several of the head strong young men who composed a portion of the passengers, and who it seems had sacrificed too freely to the Bacchanalian god, insisted upon being put over, and two of them, Robert Bartington and William Davidson, forcibly seized the oars from the boatmen, and heedlessly dashed into the stream. The boat now contained at least fifteen individuals, among whom were three females, we say at least, because some doubt exists whether another female with an infant in her arms, was not also in the boat. With such a load, the boat could not be more than four inches out of the water; the tide, running from seven to eight knots an hour, swept the boat with the greatest rapidity up to Aston stage, where it struck the stern or bows of the sloop Thetis, with a violence which instantly upset the boat, and plunged the passengers into the watery element. The shrieks of the unhappy people were at this moment most appalling but they presently subsided, the poor creatures bring driven under and against four other vessels lying in the river near the spot. The hands on board these vessels lost no time in manning their boats, but comparatively little help could be afforded, the tide passing, to use the sailors' words, like lightning.

Through their indefatigable exertions, however, four individuals were rescued from a watery grave, - viz. Thomas Latham, one of the ferry boys, and Robert Price, of Kelsterton, taken in on board the Thetis: and Frank Toliett, of Shotton, and Benjamin Bethell, the other ferry boy, on board the Speedwell. These were the only persons who escaped the melancholy fate of drowning. As soon us the catastrophe could be known, the boatmen of the sloops were joined by fishermen in the immediate neighbourhood, who continued during the whole of the night searching for the missing bodies, and by seven o'clock in the morning, four had been taken out of the water, dead. Since then, the body only of a female has been discovered, which was found on Tuesday evening on one of the grinds on the Flintshire side, nearly five miles further up the river from the spot were the fatal accident happened, and which was left there on the receding of the tide.

The names of the persons whose dead bodies have been rescued from the river,

are as follows:

William Roberts of Buckley,

Robert Bartington of Saltney,

Ellen Hulse, of Saltney,

Ann Hulse, of ditto,

Sarah Lewis, of ditto.

The two Hulses were sisters, and with Sarah

Lewis, lived under the same roof. Roberts has left a wife and seven children,

and she is also near her confinement of the eighth; and Bartington an

aged father and mother, who were in a great measure dependant

upon him for subsistence. It is impossible to describe the heart-rending

scene which the shores of the Dee presented on the morning of Tuesday. The

news of the accident had brought numbers together, among whom were groups

of the friends and relatives of the unfortunate sufferers, making solicitous

enquiries after their fate. There are known to be six still missing,

independent of the woman and infant, concerning whom as before noticed,

there are some doubts. Their names are,

Abel Ball, of Wepre,

Thomas Read, of Mancott, farmer,

William Davidson, ship-carpenter, Ewloe.

Joseph Jones, of Buckley.

Robert Jones, of Shotton,

Edward Jones, of Shotton.

Thus has perished from intemperate indiscretion eleven individuals,

respectable and useful members of society.

The drags of the humane society, and muscle[sic: mussel] and fluke rakes have been employed from Chester to Connah's Quay, in search of the remaining six missing bodies, but without success, and it is feared the tides may have sanded them. Many of the fishermen and other individuals deserve great praise for their exertions on this occasion; but considering the number of opulent individuals, who reside in the neighbourhood, and the interest which the River Dee Company ought to feel in so melancholy an event, it is to be lamented that more prompt and early efforts were not made to discover the bodies, by offering such premiums as would have induced a more active and efficient search. The condition of the boat, and the mutilated state of the oars, have been represented as highly defective. Of this, however, we know nothing but by vague report, but we have no doubt, if such be the fact, the humane agent of the Dee Company will feel it to be his duty to pay a proper regard to them for the future. We have learnt that a subscription has been set on foot, commenced by the highly respectable Rector of Hawarden, to remunerate the labours of men to be employed to search for the remainder of the dead bodies.

Boating Disaster on the Dee. A Family of 3 Drowned. 1884

Another ferry accident at Queensferry:

A sad boating accident occurred on the Dee, at Queensferry,

late on Saturday night [20 December 1884], which cast a gloom over the

inhabitants of Hawarden, Queensferry, and district, and which resulted

in the loss of three lives. It appears that a Christmas draw was being

held at the Ferry House, a public-house kept by Miss Gregory, on the

Cheshire side of the river. The draw was attended by a number of

persons from the Flintshire side, and at about a quarter past ten, most

of the party started across the river on the return journey. The party

included Robert Jackson, a cooper, together with his wife and his son,

three years of age; Robert Catherall; John Catherall, a porter at

Queensferry Station; Henry Hough, weighing-machine clerk at Ashton Hall

Colliery; Samuel Roberts, a labourer at Sandycroft Foundry; Joseph

Latham, labourer at Connah's Quay Chemical Works; John Massey, labourer

at Turner's Chemical Works; John Davies, labourer at the same works;

Samuel Edwards, coachman and gardener, in the employ of Mr. Rowley, Dee

Bank and John Jones, the boatman.

At the point of crossing, the river is about 100 yards wide,

and when the party had accomplished half the distance, John Catherall

stated to Jones that the boat was filling with water. Almost

immediately after he made the remark, the boat sank, and twelve persons

were struggling in the water. The shouts for assistance proceeding from

the men, and, above all, the piteous cries of the drowning woman are

described as heartrending. Most of the party, several of whom could not

swim, succeeded in gaining the shore by the aid of the two oars. Robert

Catherall's escape was marvellous. The poor fellow has only one arm,

but during his struggle in the water he seized the boatman's coat tail

with his only hand, and was so towed safely ashore. John Catherall,

owing to the darkness, swam a long distance in the direction of the sea,

and it was almost too late when he found out his mistake, for he reached

the shore in a perfectly exhausted state. The Jackson family, however -

father, mother, and only child - were drowned, and though the river was

dragged throughout Sunday, not one body has yet been found. A woman's

bonnet, supposed to be Mrs. Jackson's, was discovered on Sunday

morning. The boat belongs to the River Dee Company, and is described by

the survivors, who were ignorant of its condition before they embarked,

as unfit to carry such a number of passengers.

Here are detailed reports of the inquest into this

accident from contemporary newspapers.

There was, for many years, a ferry service from Parkgate to Fflint (or to Bagillt) on the Welsh shore. Also, at low tide, it was possible to cross on foot. Here I collect contemporary newspaper reports of several fatal accidents.

Another Dee Ferry accident 1799

Wednesday the 18th December 1799: the Friends passage-boat was, in

consequence of carrying too much sail in a gale of wind, overset on her

passage from Flint to Parkgate, by which accident two women (passengers)

were unfortunately drowned: two boatmen, by clinging to the mast, were

fortunately saved, and taken up. There was another passage boat in

company with the Friends, but at too great a distance to save the

unfortunate sufferers, one of which, an industrious widow, has left a

family of six children; the other passenger was a young woman, going

into service. This fatal accident, it is hoped, will in future be a

caution to the carrying of too much sail, as has been the case for some

time past, in consequence of the Flint and Parkgate boats endeavouring

to out-sail each other, to the great danger and terror of the

passengers.

Accident crossing the Dee 1821

Early on Friday morning[10th August], a man and his wife, with a young

child, ventured on an attempt to cross the sands from Parkgate to Flint

with a horse and cart loaded with herrings. This is something done at

low water by persons who are particularly conversant with the track,

though at the best a hazardous undertaking. In this present instance,

it proved fatally disastrous to the whole party who were all drowned.

Inspiration for "Mary called the cattle home"?

Charles Kingsley's 1850 Novel Alton Locke contains words created to

accompany a melancholy air:

Mary, go and call the cattle home, And call the cattle home, And call the

cattle home, Across the sands of Dee; The western wind was wild and dank with

foam, And all alone went she.

The western tide crept up along the sand, And o'er and o'er the sand, And

round and round the sand, As far as eye could see. The rolling mist came down

and hid the land: And never home came she.

Oh! is it weed, or fish, or floating hair? A tress of golden hair, A drowned

maiden's hair, Above the nets at sea? Was never salmon yet that shone so fair,

Among the stakes on Dee.

They rowed her in across the rolling foam, The cruel crawling foam, The cruel

hungry foam, To her grave beside the sea: But still the boatmen hear her call

the cattle home, Across the sands of Dee.

This poem (it has no title) became better known from a silent film of 1912 called "Sands of Dee". In

the book Alton Locke, the inspiration is said to be "a beautiful sketch

by Copley Fielding, if I recollect rightly, which hung on the wall - a

wild waste of tidal sands, with here and there a line of stake-nets

fluttering in the wind" and overhearing others discussing it "One of

them had seen the spot represented, at the mouth of the Dee, and began

telling wild stories of salmon-fishing, and wildfowl shooting - and then

a tale of a girl, who, in bringing her father's cattle home across the

sands, had been caught by a sudden flow of the tide, and found next day

a corpse hanging around the stake-nets far below".

The most likely sketch

is actually of "A View of Snowdon from the Sands of Traeth Mawr, taken

at the Ford Between Pont Aberglaslyn and Tremadoc" by Copley Fielding in

1834. This was transposed by Kingsley to the Dee Estuary. Although

Kingsley was a Canon of Chester Cathedral from 1870, when he wrote the

poem in 1850, he can only have visited the area briefly, staying with

relatives; his aunt Lucretia Ann married James Wills of Plas Bellin

[between Northop and Oakenholt] and the Kingsley family was originally

from Cheshire [the village of Kingsley is a few miles SE of Frodsham].

However, it is plausible that it was based on a real tragedy: Cattle were grazed on the salt marshes near Parkgate and Neston. The fishermen would have retrieved the body. Although, no record of such a loss has been found. In the book, the inspiration is quoted as "that picture of the Cheshire sands, and the story of the drowned girl".

Boat Accident at Parkgate 1864

At twelve o'clock on Friday night last[27 May 1864], a distressing boat

accident occurred at Parkgate, which has cast a complete gloom all over

the district and thrown several highly respectable families into

mourning.

It appears that at ten o'clock on Friday morning a party of

five [plus the boatman] took an excursion into Wales, crossing the river

Dee from Parkgate to Bagillt, in Flintshire. The party consisted of Mr

Thomas Johnson, proprietor of the Pengwern Arms Hotel, or Boathouse, at

Parkgate; his brother Mr Joseph Johnston, a landing-waiter belonging to

her Majesty's customs at Liverpool; Mr J. F. Grossman, secretary to the

Liverpool Licensed Victuallers' Association and Mr J. H. Holland and

Mr Frederick Holland (brothers), of Chester, who had been staying at

Parkgate during the last fortnight making a Survey of the channels of

the Dee.

Their intention was, if possible, to return with the same

tide. The weather was, however, so calm that upwards of an hour and a

half was occupied in crossing; and finding that they could not return by

that tide, the party landed at Bagillt and walked to Holywell, where

they spent the day. At ten o'clock the company left Bagillt in the boat

on their return to Parkgate. It was moonlight, with a steady breeze,

and a pleasant voyage was anticipated. The boat made a rapid passage,

but on arriving within a short distance of the Cheshire side it was

found that the jetty was covered with the tide, which was just beginning

to ebb, and the wind having freshened considerably a heavy swell

rendered it imprudent to attempt to get alongside the river wall. The

boat accordingly lay-to for an hour, awaiting the receding of the tide.

It was then determined to endeavour to effect a landing in a small boat

or punt which lay at anchor a short distance from the shore, and which,

it was thought, would be more manageable. One of the gentlemen, it is

said, called out that the punt would not carry them all with safety; but

this intimation of danger seems to have been disregarded, and five

persons, including Richard Evans, the boatman, got on board. Mr.

Thomas Johnson, who was a stout, heavy man, was the last to leave the

larger vessel, and no sooner had he placed his feet on the side of the

punt than the little craft capsized, and the whole party were

precipitated into the water.

Thomas Johnson, a young man about 20 years of age, eldest son

of Mr Thomas Johnson, was standing on the esplanade waiting the arrival

of his father and his friends, and witnessed the melancholy accident,

but, in consequence of the strong current that was running,

could render little or no assistance to the unfortunate persons who were

struggling for their lives in the water. Mr J. H. Holland, who had

remained in the large boat, being a good swimmer, immediately stripped

and jumped into the water and swam to the assistance of one of his

unfortunate comrades. He was unable to reach him, however, and after

several ineffectual attempts he made for the shore, which he succeeded

in reaching in a very exhausted state. Mr Frederick Holland also

managed with difficulty to reach the shore. Mr Crossman, although not a

swimmer, struck out in the best way he could, and fortunately gained the

land in safety; he afterwards received very kind attention from the

landlady of the Union Hotel, and a gentleman who happened to be staying

at the house. Richard Evans was taken out of the water in an exhausted

state. Mr Thomas Johnson was also taken out of the water alive, and was

removed to the cottage of Evans (that being the nearest house), but he

was so much exhausted that be never rallied, and death ensued before the

arrival of a medical man. Mr Joseph Johnson was carried down with the

current and was drowned. His body was found near Heswall - fully a mile

from where the disaster occurred - at five o'clock in the morning, and

removed to the Pengwern Arms Hotel, where it was placed in the same

apartment with the corpse of his brother. The boatman, Evans, was so

much exhausted by his immersion that he was not considered out of danger

until late on Saturday.

Mr Thomas Johnson was about 50 years of age, and was highly

respected at Parkgate and in the Hundred of Wirral generally. Besides

being the owner and landlord of the Pengwern Arms Hotel, he was

proprietor of the omnibuses plying between Parkgate, Hooton, and

Birkenhead Ferry. He has left a widow and eight children. His brother,

Mr Joseph Johnson, as has been already stated, was a landing-waiter

belonging to the Liverpool customs, and resided in Crown-street. He has

left a widow and four children.

The catastrophe has produced quite a mournful sensation at Parkgate and

Neston, and on Saturday and Sunday the blinds were drawn in a great

number of the houses in the locality.

At the inquest, on Monday, the jury returned a verdict to the

effect that deceased were accidentally drowned, the verdict being

accompanied with a presentment that in the opinion of the jury the

landing stage opposite the Pengwern Arms was too low, too short, and

quite insufficient for the landing of passengers at certain states of

the tide.

Back to top

Wreck of wooden vessel alongside staging in canalised portion of River Dee

This view shows the wreck of a 20th-century

timber coastal vessel registered at Peterhead, Scotland. She now lies aground

next to a substantial timber landing stage on north-east bank of the River

Dee, at Hawarden Bridge, above Connahs Quay at 53° 13.179'N, 3° 2.329'W.

Back to top

Wreck of 13.5m Fishing Vessel AUDREY PATRICIA alongside the

scrapyard berth at Connahs Quay.

Image of Audrey Patricia afloat.

She was reported to have sunk at her moorings on 2 Dec 2012 in

position 53° 13.332' N, 3° 3.589' W with about 50 litres of

diesel released.

She was registered as LN486 [Kings Lynn] with shellfish

licence, 30 tons register, steel hull, 216 hp, built 2008 at Barton-on-Humber.

The wreck is scheduled to be removed on 1 Oct 2018.

John Lake of Kings Lynn, was fined a total of £15,628

in July 2018 after being prosecuted by the HM Coastguard for operating

an unsafe vessel [called Audrey Patricia but registered as LN89 - so

presumably a different vessel] and failing to comply with the small

fishing vessel code of practice. She had been inspected at Boston and

found to have many serious deficiencies.

Back to top

Wreck of steam barge Lord Delamere 131 tons. Wooden hull, length 86 ft, width 20ft, draught 9ft. Owned Salt Union then Joseph Forster of Liverpool. Built Ann Deakin, Winsford. Engines 2cyl, 1 boiler, 24 h.p., screw by G. Deakin. Crew 3.

For more detail of the circumstances of the loss, see report .

From Flintshire Observer 16 Oct 1913

AGROUND IN THE DEE. Mishap to Steam Barge.

The steam barge, "Lord Delamere," hailing from Liverpool, grounded on Tuesday [13 October 1913] opposite the North Wales Paper Mills, Flint [at Oakenholt]. It was heavily laden with grain for the Cobden Flour Mills, Wrexham, and was proceeding to Connah's Quay. During high water only the masts are seen, but at, low water yesterday some of the grain was unloaded by smaller vessels. It is feared that the barge will become a total wreck, having been badly strained.

Her grain cargo swelled which burst her hull and she was a total loss. She is on the SW bank opposite the North training wall. She had been under the charge of a Dee Pilot (William Taylor) and a court case was initiated against the Dee Conservancy, but not followed up.

This wreck was marked by a

buoy in the 1930s which was discontinued. A mast was visible in the 1980s.

Because of changes to the channel which is shifting SW, it was marked again

from 2013 by an

Isolated Danger Buoy (red+black) at 53° 14.31' N, 3°

5.32' W near the wreck position.

Back to top

Brigantine Baron Hill 224gt, 198nt, registered Liverpool.

Built William Thomas, Amlwch, 1876 224gt, 198nt;

119ft length x 25ft breadth x 13ft 4in depth; 1 deck, 3 masts

Owned William Postlethwaite of Millom.

The three-masted schooner BARON HILL (named after an estate

near Beaumaris) was built at Amlwch in

April 1876 and was owned by Millom's William Postlethwaite from 1876

until her loss on the 26th March 1898. Travelling from Flint to

Newcastle with a cargo of salt cake, the Baron Hill was towed out and

then stranded and lost in wind conditions ENE Force 6 in the Dee estuary

2 miles from Flint. The master was Capt. L. Hughes and there was a

crew of six. Her crew managed to get safely ashore. Within two days

she was a total wreck and being stripped.

Contemporary newspaper report:

On Thursday a severe gale from a north-easterly direction commenced to blow at this port [Connahs Quay], and continued throughout Friday and Saturday. On the wharves the full violence of the storm was felt, the cold being intense and snow falling at intervals. During high water at the docks on Thursday the river presented a turbulent appearance, and ships that had completed loading were quite unable to move out. The same difficulty was experienced on Friday, but steam tugs were employed, and a few of the ships succeeded in getting into the river after a most exciting time. On Friday's tide a large schooner, named the Baron Hill (350 tons burthen), loaded with a cargo of salt cake from Flint to Newcastle-on-Tyne, left the former place in tow of the steam tug Manxman in the teeth of the gale in the hope of safely reaching deep water in the Wild Roads. She had not proceeded far when she grounded in the river, and all efforts during the following night's tide to get her off proved unavailing. It is said that during Sunday a large amount of water was in the hold, and the crew had to leave the ship. One of the masts has been carried away, and it is feared the ship will break up and become a total wreck.

The wreck was shown on the HO chart (1978) until the 2000s in

position 53° 16.65' N, 3° 8.45'W (OSGB36 datum). This is about 2 miles

North of Fflint. She was marked by a

wreck buoy until 2002. After inspection at LW, the wreck is now classified as

"dead". The wreck buoy was marked "Barron Hill" - a different spelling.

Back to top

Pre-war aircraft lost in Heswall tidal gutter:

Airco DH

9a

light bomber, no E8628, from RAF Shotwick [later renamed Sealand]

Mainly built by Westland, with the US Liberty 12 engine of 400 hp,

2-seater.

Flying School No. 5: pilot - trainee Robert Cecil Brooke-Hunt, age

25.

26 March 1923, broke up in the air and fell in 3 parts

Parts landed in Heswall tidal Gutter, approx: 53°19.49N,

3°7.44W.

Pilot died.

Full Details.

Image of a DH 9A:

Records of losses of RAF

aircraft in the Dee Estuary (in date order, during and after World

War II). There were nearby airfields at Sealand

and Hawarden and many training flights [OTU and FTS are training

operations], some of which ended badly. Training extended from initial

flight training up to combat training using targets near Talacre (both fixed targets

in the dunes and aircraft-towed targets; some targets may have been drones - the

DH Queen Bee, a radio-controlled Tiger Moth, being the original "drone").

There was also a radio school (11 RS; radio included

radar) based at Hooton Park airfield nearby - which used twin engined planes for

in-flight training. Metal was in short supply during the war, so crashed

aircraft would have been salvaged whenever possible. Much use was made

of wood and canvas in aircraft construction, so little may remain.

Note that missing air-crew are inscribed on the Memorial at Runnymede.

Anson N5234: 3-1-1940 502 Sq., stalled, spun and crashed onto the foreshore about 4 miles east of Rhyl, soon after take off from RAF Hooton Park, Cheshire, in a snow storm for a night patrol. Possible cause of accident was ice on wings. All 4 crew survived, although Corporal H C Moody was injured. Ambulance took 7 hours to reach the scene. Aircraft destroyed. Image of N5234 in foreground

Hawker Hind K6758: 4-3-1940 5 FTS. Acting Flying Officer Russell BELL (70791) was ferrying a Hind biplane (used as a trainer) when he lost control and it dived into the ground at Hoylake beach. He was aged 26 and is buried at Wavertree (Holy Trinity) Church.

Spitfire L1060: 28-8-1940 7 OTU, stalled and dived out of steep turn, entered at between 2,000 and 3,000 ft. Did not recover, crashed onto beach at Hoylake. Aircraft written off. Pilot P/O(42136) Michael Ernest Brian MACASSEY, from New Zealand, age 23, buried Hawarden (St. Deiniol) Churchyard.

Spitfire K9981: 12-9-1940 7 OTU forced landing on mud flats in River Dee

near Flint, written off.

Lost River Dee mouth, Flintshire on 12th September 1940, Pilot Sgt Alexander Noel

MacGregor (740705) uninjured. Pilot transferred to 266 Squadron later in Sept 1940.

Miles Master N7944: 24-9-1940 5 FTS abandoned in a spin and crashed into Dee estuary. No record of fatalities, so crew may have baled out.

Miles

Master N7965: 20-12-1940 57 OTU, flying accident: Pilot Officer

Harold Edwin Hooker 85920 died (age 27, grave St Deiniol, Hawarden); Leading

Aircraftman D G Northwood injured.

Near Hilbre Island, 20-12-1940, a boat from the yacht club was

manned and put out to an aircraft that had dived into the sea. One

person was rescued, the body of another was recovered later.

Anson R3303:

1-1-1941 48 Sq. With a crew of 4, it was returning from a convoy

patrol to base at RAF Hooton Park, when the wing hit the ground during a

turn in bad visibilty and the aircraft crashed onto the beach at

Hoylake, Cheshire. All on board were killed:

Pilot Officer John Hogg ERSKINE (81034) Pilot; Sergeant John

Llewellyn CURRY (748639) Pilot; Sergeant William Edward FENNELL (966641)

Air Gunner; Sergeant William Charles LANGDON (751603) Wireless Op.

Hurricanes V6872 and W9307: 30-3-1941, mid-air collision between 2

aircraft from 229 Sq. (Ship protection, based RAF Speke) at sea off

Prestatyn. They were flying a standard patrol at 13,000 ft. At 12:20

radio communication ceased and Royal Observer Corp reported a loud bang

at 12:28. Hoylake and New Brighton lifeboats searched but found

nothing. On the 31st March 1941 three pieces of wreckage were found by

the Coast Guard at Hoylake, these pieces were picked up on the beach at

Hilbre Island and were confirmed to belong to Pilot Officer Du Vivier's

Hurricane W9307. This, together with the fact that Hoylake and New

Brighton lifeboats (but not Rhyl) were alerted, suggests the collision

was over the Hoyle Bank off Hoylake rather than off Prestatyn.

Both pilots missing believed dead: Flying

Officer John Michael Firth DEWAR (72462) age 24; Pilot Officer Reginald

Albert Lloyd Du VIVIER (79370) age 26.

Spitfire X4065: 11-8-1941 303 Sq (Polish AF from RAF Speke). Pilot Officer Stanislaw Juszczak (P-0386 age 23) on training flight - possibly cockpit froze over in clouds - and he lost control. Aircraft dived into sea near Prestatyn (3 miles off). Rhyl lifeboat searched area but found nothing - pilot's body not recovered.

Spitfire K9995: 21-9-1941 57 OTU hit mudflats in Dee Estuary, total

wreck.

Royal Humane Society Award citation to Mr Prior (one of the rescuers) at a

location described as near Neston, Wirral:

While engaged on flying

practice over the coast, the pilot of a Spitfire fighter pulled out of a dive

too late and the tail of the aircraft struck the surface of the water, a

portion breaking away and the remainder travelling over the surface of the

water for some 100 yards before it burst into flames and sank. A very strong

current was running, the tide was on the ebb and the rescuers had to swim for

some 20 minutes before they reached the pilot. They then brought him ashore

where it was found that he had no injury other than the shock and the effects

of the immersions. The GOC-inC offers his congratulations to those men on the

Gallantry and excellent spirit shown. West Command Order 2087, dated 21

November 1941.

Pilot was Czech - Sgt K Janata, 788040.

When low flying, hit mud flats and crashed, pushed control column

forward when checking plug in's for R/T, injured.

Hurricane P5188: 13-3-1942 MSFU landed on Hoyle Bank and was

rescued:

Flying Officer John Bedford Kendal (83268) of the Merchant Ship

Fighter Unit [based at RAF Speke this unit provided catapult-launched

Hurricanes to suitably equipped merchant ships - though recovery of the

plane by those ships was not available] was carrying out formation

flying in Hawker Hurricane P5188 when his engine failed - reported to be

because of neglect to switch fuel tanks correctly. He had to make

a wheels-up forced landing on West Bank[sic], Hilbre Island 3 miles West of

West Kirby at 16:00 hours, the aircraft was subsequently immersed by the

sea. Flying officer Kendal was uninjured. photo.

At about six in the evening of 13th March, 1942, a Hurricane

aeroplane made a forced landing on the West Hoyle Bank. A moderate wind

was blowing from the S.E., with a slight sea, but the tide was flowing

and the bank would be covered in two hours' time. The lighthouse keeper

of Hilbre Island and an airman put off in a rowing boat to the rescue.

They had a hard row for about a mile and a half, but they reached the

bank in good time and rescued the pilot. It was another hard row back,

and the night had come before they reached the lighthouse. The

lighthouse keeper's wife put up the rescued pilot for the night.

Hurricane: 15-3-1942 was found on East Hoyle Bank by Rhyl

Lifeboat with no trace of her crew.

Spitfire K9864: 8-5-1942 57 OTU, air collision with spitfire R6769 (which managed to get back to Hawarden) crashed bank of River Dee near Flint, pilot injured,

Anson EG447: 17-7-1942 11RS, crashed into sea NW of Rhyl with 2 out of 4 crew lost. More details.

Spitfire N3276: 10-8-1942 57 OTU stalled, spun and crashed into River Dee

at Saltney Ferry, near Hawarden.

Pilot: killed on active service,

Sgt (Pilot) Gordon ROSENTHAL (age 22, death registered Hawarden) - 655729 -

buried Liverpool Hebrew Cemetery.

Blackburn

Botha Mk I L6237: 8-1-1943 11 Radio School, ditched in bad weather

near Bagillt in Dee estuary.

On 9-1-1943, 4 airmen from a plane from Hooton Park RAF Aerodrome

[Wirral] were reported

overdue and were spotted and recovered a quarter of a mile N. by E. of the Dee Buoy

at about 13:00 by the Hoylake Lifeboat after spending a night (since

6pm) afloat in their small dinghy.

Spitfire P7430: 29-1-43 61 OTU crashed, attempted forced landing

after engine failure, near Mostyn, Flintshire. Crashed, aircraft written off.

[crash site may have been on land]

Pilot Sergeant John Hugh DYER (1385327, age 21) buried

Hawarden (St. Deiniol) Church.

Mustang AP216: 5-2-1943 41 OTU crashed into Welsh Channel, pilot killed. Pilot Officer David Shingleton-Smith (127950, age 19) of 41 OTU was killed on 5 February 1943 when his Mustang Mk I AP216 hit a pole and crashed into the sea at Prestatyn Ranges [Talacre], Flintshire. Rhyl lifeboat searched but found no trace.

Spitfire P7692: 26-7-1943 61 OTU crashed at Talacre. The pilot was engaged in air-to-ground firing practice at Talacre Warren. The aircraft crashed into the target, coming to land amid the anti-invasion poles on the seaward side of the minefield. No record of pilot fatality.

Mosquito

HX867: 14-2-1944 60 OTU. Crashed into sea off Prestatyn during air

firing practice. Based 60 OTU, RAF High Ercall, 7m NW of Shrewsbury,

that trained "intruder" crews. Both the Canadian airforce crew lost.

Shortly after eleven in the morning of the 14th of February, 1944, a

Mosquito aeroplane crashed in flames half a mile south-by-east of

Chester Flat Buoy. A light north-west wind was blowing. The sea was

fairly calm. Mr. A. O. Jones saw the accident, and with help carried

a boat from his garden and launched it. It was a 12-feet skiff and not

built for use on the sea. Mr. Jones and another man, Mr. J. McWalter

Shepherd, put out in it, but were unable to give any help.

At 11.09 in the morning, the Rhyl coastguard reported that an

aeroplane had crashed in the sea about a mile north of the coastguard

look-out. The Rhyl motor life-boat, The Gordon Warren, was launched at

11.49, and half an hour later found wreckage of an R.A.F. Mosquito

aeroplane two and a half miles north-north-east of Rhyl. She picked up

a body, badly damaged as by an explosion, and took it to Foryd Harbour.

She then made another search, found landing wheels and other wreckage,

and brought them in, returning to her station again at 6.15 that

evening.

Location: Off Prestatyn: 53°21.3N, 3°27.0W

approx.

Casualties:

Flight Lieutenant William Ernest CULCHETH (J/4815) Pilot Mosquito

HX867, RCAF lost 1944-2-14 (age34) 60 OTU, Runnymede Memorial Ref :

Panel 244.

Flying Officer Earl Frederick MORTON (J/16333) Navigator Mosquito

HX867, RCAF lost 1944-2-14 (age 28) 60 OTU, buried Chester (Blacon)

Cemetery.

Spitfire X4173: 19-5-1944 52 OTU,

stalled pulling out of firing dive and crashed on Prestatyn ranges at Talacre.

Off Talacre, on 19-5-1944, a Spitfire X4173 had crashed into the

sea near the S Hoyle buoy. Rhyl lifeboat had been launched, but then a

report of a more accurate position (near the lighthouse at Talacre -

with tail visible) led to the auxiliary rescue-boat from Llanerch-y-Mor

being sent - without being able to recover the wreckage or pilot.

Pilot: Polish

Kapral Feliks WARES (P/703726, age 26) buried Hawarden Cemetery

Martinet HP242: 17-7-1944 41 OTU, used primarily for target towing, crashed at Llanerych-y-Mor (one mile SE) (a local sailing dinghy rescued one, the RAF rescue-boat rescued a second; pilot S Dudek, Polish AF)

Spitfire BM113: 24-7-1944 61 OTU hit target drogue, crashed into sea SW of West Kirby.

Off Talacre, on 24-7-1944, Spitfire BM113 hit a drogue during firing practice,

sank, pilot lost. Auxiliary rescue-boat and Rhyl Lifeboat were called

out but a fishing boat reported that the aircraft had nose-dived into

deep water with no trace of the pilot.

Pilot Flying Officer Arthur Jacob GOLDMAN (J/38019) RCAF officially

presumed dead when his aircraft hit a target towed by another aircraft.

Hurricane LF369: 31-12-1944 41 OTU was wrecked in the Dee off Fflint. Pilot Douglas Richard Kyrke NUSSEY F/O(P) J43333/R207038 from Hudson Heights, Quebec, age 20, lost his life when his Hurricane aircraft LF369 crashed four hundred yards off shore, one mile north of Flint. Body not recovered.

Anson EG186: 15-3-1945 No. 3 (Observers) Advanced Flying Unit, based at RAF Halfpenny Green in Shropshire, ditched at Llanerch-y-Mor (300 yards off) crew saved, airframe later salvaged.

Spitfire PK385: 21-5-1950 610 Sq., during aerobatics, hit sandbank 3 miles east of Point of

Ayr, scrapped, pilot died.

A Spitfire on a training flight from 610 Squadron at RAF Hooton

Park (Wirral) crashed into the sea at Gronant (near Prestatyn) - so

avoiding the many holidaymakers on the beach. The pilot, Sgt. Kenneth John

Evans, aged 25, was killed.

Chipmunk

WB747: 20-7-1954 63 Gp, entered flat spin and hit Bagillt sandbank 1

mile north west of Flint.

TWO SAVED FROM PLANE ON SANDBANK: Two occupants of a

Chipmunk plane from Hawarden R.A.F. Station had a remarkable escape

when they crashed on to a sandbank on the six miles-wide estuary of the

River Dee at Flint yesterday[20-7-1954], fortunately the tide was out at the time.

The injured men were trapped in the cockpit and would have been drowned,

as the aeroplane was completely submerged when the tide came in again

two hours later. The plane was piloted by Group Capt. H. C. S.

Pimblett, senior medical officer of No. 63 Group. R.A.F., Hawarden.

His A.T.C. Cadet passenger J. S. Howell. belongs to No. 2219

(Greenhall Grammar School) Squadron, Tenby, Pembrokeshire, which is in

camp at Hawarden. Although the plane crashed some distance from the

shore, rescuers were quickly on the scene, the first being Evan Andrews

of Queen's Avenue, Flint; Davis Barker, Salisbury Street, Flint; Ronald

Hilton, Chester Street, Flint; and Hugh Fox, Henry Taylor Street, Flint;

who were working on the roof of a local factory.

CROSSED QUICKSANDS: They saw the plane coming down in a spin

at a height of about 100 ft. and it disappeared out of sight over the

marshes of the river. The four immediately left their work, and after

removing their shoes and socks, they crossed a considerable distance of

marsh land, and about a mile of treacherous quicksands, to reach the

plane, which had made a pancake landing on the edge of the deep water

channel. The four men were joined by Police-constables J. Harris and

M. Harris, of the Flint Police, and they found the two occupants of the

aeroplane injured and trapped in the cockpit. To release them the

rescuers had to rip away the hood and a part of the cockpit dashboard

and controls with their bare hands. They were joined by members of

Flint Fire Brigade, who assisted in the work of extricating the men.

EQUIPMENT REMOVED: Police-inspector B. Roberts, Flint,

organised stretcher parties and the injured men were carried a

considerable distance to a waiting ambulance which conveyed them to

Flint Cottage Hospital, after medical attention on the spot. High

ranking R.A.F. officers with personnel arrived on the scene but, in a

race with the tide, found it impossible to salvage the aeroplane because

of the incoming tide. A quantity of equipment and some instruments were

removed. Before leaving the scene, Wing Commander Fraser personally

thanked and complimented those who had taken part in the rescue.

Information from RAF records and from RNLI(Rhyl and Hoylake) and RAF rescue-boat records list for

1940,

1941,

1942,

1943 and

1944.

Many call-outs to reported aircraft crashes in the sea

were for searches that found nothing.

Also a German aircraft wreck: A Heinkel 111 (No. 2874) was shot

down by a

Defiant from RAF Squires Gate [Blackpool] and the wreckage landed on Bagillt marshes

on 7-5-1941. Image of wreckage:

This area is now covered in mud. More detail.

Back to top

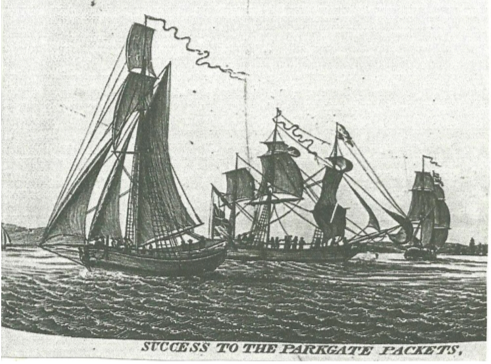

Parkgate was an important point of departure for passenger ships

travelling to Dublin. The Parkgate Packets were sailing ships (mostly

two masted) that could take the ground. A Packet service meant a

regular (as weather allowed) service which took passengers (it did not

carry mails in this case - those went via Holyhead).

They also took cargo. There was a good road

link from London to Chester and a coach service from there to Parkgate

which had hotels and other facilities. Many famous people: Handel

(returning from Dublin in August 1742); Rev. John

Wesley (many times), Jonathan Swift (from

Dublin 1707, return 1709), etc used this service. Parkgate was an anchorage and the packet vessels were

loaded and unloaded using boats from two wooden piers.

Shipbuilding at Parkgate.

The Dee Estuary up to Parkgate in 1771 (South up) from Burdett's Chart:

The Royal Navy provided a service, using Royal Yachts which was intended for distinguished persons, although they took extra passengers at the Captain's discretion. Commercial interests (such as John Bibby of Liverpool, among others) also provided vessels in this trade. A crossing took at least 14 hours. In 1795-6 about 80 such voyages a year were recorded (in vessels Prince of Wales, Princess Royal, King, Queen, Lady Fitzgibbon). The service was at its peak around 1790 and had dwindled by 1830 when a good road to Holyhead (with a much shorter sea crossing); steamship service from Liverpool and the silting up of the Dee, all curtailed activities.

See image of Royal Yacht Portsmouth which provided a service from 1679-87.

Image of Parkgate-Dublin Packet ship Royal Yacht Dorset leaving Dublin, 1788:

There were several significant shipwrecks in this service. Only one (King George) occurred wholly within the Dee estuary; while two were on the Hoyle Bank which is at the entrance to the Dee Estuary. Note that a wreck within the Dee Estuary (at Hilbre Island) is recorded for a sailing packet (also named Dublin) on the Dublin-Liverpool service in 1759.

List of wrecks of Parkgate Packets (discussed below):

Unknown 1637; Anglesey, many lost

Mary 1675; Skerries, over 35 lost

Neptune 1748; Hoyle bank, over 100 lost

Dublin 1758; Irish Sea, up to 50 lost

Eagle 1766; Irish Sea, more than 10 lost

Nonpareil 1775; Hoyle bank, over 100 lost

Trevor 1775; off Blackpool, over 30 lost

Charlemont 1790; Holyhead, 110 lost

Queen 1796; off Birkdale, 0 lost

Queen 1799; Dublin, 14 lost

King George 1805; Dee, 125 lost

Prince of Wales

1807; Dublin, 120 lost

Packet 1637: A Packet(name unknown) from the Dee Estuary

(starting location named as Chester) to Dublin was lost on 10 August

1637. It was carrying Edward King, aged 25, a fellow of Christ's

College Cambridge, an acquaintance (and previously a fellow student) of

the poet John Milton. King was travelling to visit his brother and two

sisters in Ireland. The vessel was coasting in weather [variously

described as calm and as stormy] along the Welsh shore, when it struck

on a rock, was stove in by the shock and foundered. The most likely

area, where rocks would be close to the vessel's route, is the north

coast of Anglesey. With the exception of a few who managed to get into

a boat, all on board perished.

King is said to have behaved with calm heroism; after a vain

endeavour to prevail upon him to enter the boat, he was left on board,

and was last seen kneeling on deck in the act of prayer. His body was

not recovered. John Milton wrote a poem, Lycidas, published in a

collection of elegies in memory of Edward King. This poem is regarded

by many as one of the finest in the English language.

Mary 1675: The (ex - Royal Yacht) Mary was used to carry dignitaries between the

Dee to Dublin. She was wrecked on the Skerries (low lying rocky island

on the NW corner of Anglesey) in 1675 with 35 lost. This wreck has been

located

by divers and is now a protected wreck.

More details: Loss of Mary 1675

Neptune 1748:

One of the first to be documented by newspapers was the loss of the Neptune

(Capt. Whittle) on 19 January 1748. She left Parkgate with over 100 on

board and reached Chester Bar where the weather forced her to turn back.

She struck on the West Hoyle Bank with the loss of all aboard. Two

other passenger-carrying vessels left at the same time, but they managed

to get back safely to Parkgate.

More details: Loss of Neptune 1748

Dublin 1758: Another wreck occured in October 1758 when the

Dublin (Captain White; also called Dublin Trader; Dublin Merchant and

Chester Trader) foundered on a voyage from Dublin to Parkgate carrying

40-70 passengers. There was criticism at the time about the

seaworthiness of the Neptune and of the Dublin.

More details: Loss of Dublin 1758

Eagle 1766: In 1766 the Eagle (Captain Sugars) from Dublin to Parkgate foundered

in the Irish sea. Some passengers and crew survived in her boat after 36

hours at sea. Some distinguished passengers were lost.

More details: Loss of Eagle 1766

In a letter dated 12 Nov 1771; the masters of 11 ships warn of coal ships,

trading from Ness[near Parkgate] to Dublin, claiming to be Parkgate Traders.

Those ships which claimed to be "proper" passenger packets were: Royal

Charlotte; Alexander; Britannia; Kildare; King George;

Hibernia; Nonpareil; Venus; Polly; Smith; Fly.

Note that this list does not include the Trevor - which

indeed is listed as carrying coal in ship arrival/departure lists.

Nonpareil and Trevor 1775: On

October 19 1775 the Nonpareil(Capt. Samuel Davies) and the Trevor(Capt.

William Tottie) were both wrecked in a severe storm while sailing from

Parkgate to Dublin. They reached a position close to Holyhead when the

wind increased to hurricane force from the west. This drove them back -

the Nonpareil was lost on Hoyle Bank with the loss of everyone aboard

while the Trevor was lost off the shore near Rossall (North of Blackpool)

with only one sailor surviving (who managed to transfer to another

vessel, Charming Molly, being driven towards the shore at the same time).

Passenger and crew losses were 143 in total (200 in some reports):

allocated as 113 on the Nonpareil and 30 on the Trevor.

One of the distinguished passengers lost aboard the

Nonpareil was Major Francis Caulfield (brother of Lord Charlemont) who -

ironically - had been pressing the captain to leave, even though the

Captain was reluctant because of the weather, and, indeed, only succeeded

in getting out from Parkgate at the third attempt.

These vessels were carrying items valued at £30,000

comprising rich silks, raw and thrown silks, gold and silver watches,

silver plate, plated goods, thread and silk laces, jewellery,

haberdashery wares, woollen cloth, and other valuable effects. The

Nonpareil was carrying a coach which was washed up on the north Wirral

shore with a number of silver candlesticks stowed in it.

Adverts were put in local newspapers warning that plunderers would be

prosecuted and offering a 10% reward for any items retrieved.

More details of loss of Trevor and

Nonpareil (including information on shipping damaged in the Dee Estuary).

In 1785, two Parkgate-built vessels (King and Queen) were

launched to replace the two lost - they were reported as of 100 tons

burthen. Details of maiden voyage of the

King. One of them was subsequently driven ashore on the coast near Southport:

Queen 1796: Loss of Queen 1796; Parkgate - Dublin Packet

Wooden sailing vessel, b Parkgate 1786; 100 tons

Captain Miller; voyage Parkgate to Dublin; all crew and passengers saved.

Ashore Birkdale (near Southport) 3 Dec 1796.

Local newspapers describe the Queen Packet, Captain Miller, with

passengers from Parkgate to Dublin, as totally lost on the Lancashire

Coast, near Formby.

A later report specifies the site as Birkdale Beach on the

evening of 3 Dec 1796. The Captain was highly complimented by the

passengers for his abilities and humane attention, from the time she

foundered, till they and the crew, by means of the boat, had with much

difficulty escaped the fury of the waves, and were safely landed.

Queen 1799: The Queen Packet seems to have been refloated and several

years later was then described as lost by being driven against the South

Bull wall at Dublin on 22 September 1799 as she entered the harbour.

About 14 of her passengers were swept overboard. Many of the passengers

were soldiers - of the Oxford Militia.

From Saunders's News-Letter - Wednesday 25 September 1799

The passengers on board the Queen were chiefly soldiers; she

took in water

rapidly, and a heavy rolling sea washed over her deck; in this situation

several of the passengers attempted to gain the wall, and of these

only two serjeants of the Oxford Militia were fortunate enough to

succeed, having been thrown upon the wall -- the remainder, to the

number of fourteen, have perished. Some of the dead bodies were thrown on shore

near the Black-rock and Dunleary.

Image of Parkgate Packets (from a ceramic jug):

Charlemont 1790: A substantial loss of life occured

on Sunday 19 December 1790. The Packet

Charlemont from Parkgate was unable to dock at Dublin because of

adverse weather. Scared and seasick passengers pleaded to be put ashore

at Holyhead, but the captain and crew were unfamiliar with the coastline

there. In attempting to seek shelter at Holyhead, she was wrecked on the north side of Salt

Island in the entrance to the harbour with the loss of 110 lives. Only

16 people survived.

More details of Charlemont Loss.

Prince of Wales 1807: Yet another loss of a Parkgate Packet was in 1807 when the Prince of

Wales was chartered to bring troops from Dublin to Liverpool. Along with

another vessel, Rochdale, employed similarly; they were both wrecked on

the shore between Dun Laoghaire and Dublin with a huge loss of life.

More details of

loss of Prince of Wales and Rochdale.

Note that the Prince of Wales had been involved in an earlier

accident in

1787 when John Wesley was aboard.

Back to top

The largest loss of life in the Dee Estuary was when the Parkgate to

Dublin Packet Ship King George stranded and was lost on 14 September 1806 on

the Salisbury Bank. There were 125 (106 in some reports) fatalities and only 6

were saved. One report is that 118 out of 119 passengers were lost.

Very approximate position 53° 19.5N, 3° 12.0W.

Chart of Dee from 1800 (not north up) showing Salisbury Bank:

Local comment was that the ship had too fine a bow - so would not

take the ground in a stable way. She was reported to have previously

been a privateer (of 16 guns) and then a Harwich Packet, and was on only

her second crossing to Dublin. The Harwich Post-Office Packets usually

carried 4 4-pounder guns for defence. Many of the bodies of survivors washed

up on the Wirral and Lancashire shore and some of those identified were

buried at Neston Church.

There is a record of the Hoylake Lifeboat (operated by the

Liverpool Dock Board at that time; from 1803) being called out - but unable to help.

From the Cambrian Newspaper 27 Sep 1806 and Morning Herald (London) 20 September 1806 [warning: rather racist account]:

AFFECTING SHIPWRECK. The King George packet, Captain Walker, bound from Parkgate to Dublin, sailed from Parkgate at twelve o'clock on Sunday, with a flag at her topmast-head, full tide, weather hazy, and drizzling rain, with the wind nearly directly south. At half past one she struck on the Salisbury Sand Bank, and remained nearly four hours dry, with part of her crew on the sands, waiting for the next tide. No apprehensions were then entertained of her having received any injury. On the return of the tide, the wind veered round to the west, and she received the wind and tide right on her side, resting against her anchor. As the tide came in, she filled, rapidly with water; the night was dark, with rain.Her passengers, mostly Irish harvest-men, above a hundred in number, who were going home with the pittances of their labours to their families, were under hatches. The pumps were soon choaked, and the water came so fast on the Irishmen in the hold, that they drew their large pocket harvest knives, and with a desperation that a dread of death alone inspires, slew one another to make their way upon deck. The wind and waves beating hard upon her side, her cable broke, and she was drifted round with her head towards the tide, and lay upon her side. They were three miles from any vessel, and could not, or at least did not, give any signal that was heard.

The boat was launched, and ten of the crew, among which was the Captain and an Irish gentleman, got into it. It was nearly full of water, and death on all sides stared them in the face. Her Captain seeing some of his best sailors still with the vessel, and falsely hoping she might remain the tide, which had nearly an hour and a half to flow, went again on board; the Irish gentleman and three others followed him. One of the sailors in the boat, seeing a poor Irish sailor boy clinging to the side of the vessel, pulled him by the hair of the head into the boat, cut the rope that fastened it to the vessel, and the tide drove them away.

At this time great numbers ran screaming up the mast; a woman with her child fastened to her back, was at the top-mast-head: the masts broke, the vessel being on her side, and they were all precipitated into the waves! Only five men and the poor Irish sailor boy have escaped; the remainder, 125 in number, among which were seven cabin passengers, perished. The boat and her little crew were driven up by this tide to within a quarter of a mile of Parkgate. They heard the cries of the sufferers distinctly for half an hour. The ebb tide washed the vessel down into the deep water, and she was seen no more till the next tide drove her up. She lies on her side, with her keel towards Parkgate, and her head to the Welsh coast; her lower masts and rigging out of water.

The King George packet belongs to Mr. Brown, of Liverpool; she was formerly a privateer, and carried 16 guns; was afterwards employed as a Harwich packet. This was her second voyage to Dublin, for which service she has been lately patched up. She was considered as too sharp built for the sands. Some flats are expected round from Liverpool to sweep her. None of the bodies of the sufferers have yet been found.

Her previous history:

Harwich, Jan. 8. Yesterday at six am arrived the Post-Office Packet

King George, Capt. Saunders, from Heligoland, with the Mails and

Passengers, after receiving some damage at the Island.

[Sun (London) - Monday 09 January 1804]

Private Contract. The good Packet King George, late of Harwich, river built, 83 tons per register, is well found in stores, and fit for sea. Now lying Irongate Tier[sic, wharf near Tower of London]. For Particulars apply Robert Cole, at the sign of the Crooked Billet, Irongate. [Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser - Wednesday 21 May 1806]

The King George was owned by Mr. Brown of Liverpool. There is also an unconfirmed report of a small Neston colliery vessel passing close to the wreck during the night, hearing the screams, and trailing rope in the water, by which means one of the crew managed to reach safety.

Record of 5 (out of 6) of those saved in the boat of the King

George: Henry Walker (mate, brother of Captain Thomas Walker), 2 crew

(Williams and Roberts), a blacksmith and the Irish boy. Another report

states that a woman passenger was among those saved in the small boat.

Record of those buried at Neston (thanks to Burton and Neston

History Society): Captain Thomas Walker (of Parkgate, aged 34); sailor

Hugh Williams; passengers Henry Walker and Major Phillip Armstrong of

Kings County [now County Offaly] Militia aged 39; John Ladmore (from a

local family of mariners and anchorsmiths, aged 43); Edward McQuirk and

8 "poor Irishmen".

A report from Hoylake describes 23 bodies being gathered on

the beach. 24 (unnamed, including 1 girl) were buried at West Kirby;

6(unnamed, including one female) at Heswall; one(unnamed) at Bagillt and

one(unnamed) at Fflint. There were no other wrecks involving loss of

life (although the American vessel Tippoo Saib, inbound from Savannah

was wrecked at Formby Point at the same date, but with crew rescued).

So bodies reported recovered at other sites are most probably from the

King George: 8 labourers and 2 gentlemen in Lancashire (on the coast

between Crosby and Morecambe). These newspaper and parish register

reports (which do not include the coast from Hoylake to Crosby) show

that the death toll was at least 56.

Records give 7 cabin passengers, later amended to 4; another

passenger aboard (and lost) was William Benson[Besson in one report] of

Leicestershire (who was an assistant to cattle breeder Mr Honeybourne of

Dishley) and who had 6 valuable rams aboard which he was taking to an Irish

property of his boss. His body was found near Liverpool. He was about 50

years old.

Back to top

The ferry Duke of Lancaster was intentionally run aground at Llanerych-y-mor (53° 18.393'N, 3° 14.139'W) to provide a "Fun ship" in 1979. She is now (2017) abandoned and fenced off and has recently been painted a dark colour(2018 image) to be less of an eyesore. There is a barge aground nearby (53° 18.394'N, 3° 14.116'W) - looks like a standard WWII concrete barge. Apparently an older WWI pre-cast concrete barge (Elmarine, built Fidler's Ferry) was also used - but is no longer visible..

Duke of Lancaster: report

Photos of ship and barge.

Back to top

Wooden sailing barge (Mersey Flat), ketch-rigged (also called jigger).

ON 97743, built Northwich 1863, 47 tons [110 tons deadweight], owned Clare's Lighterage Co.

Registered Liverpool, register closed 1907.

Voyage Port Dinorwic to Sankey Bridges with roofing slates.

19 February 1907; sank by collision of SS Jane while anchored

in Wild Road (Dee Estuary), off Mostyn (53°19'N, 3°15'W OSGB)

Captain John Waterworth of Runcorn and mate Richard Wainwright of Widnes: both saved

The Ant [unusual name - maybe to economise on signage?] with a crew of two [this is less than the usual 3-4 crew for Mersey Flats when in the open sea] was bringing roofing slates from Port Dinorwic [in Menai Straits] to Sankey Bridges [up the Sankey Canal accessed from the Mersey by locks at Widnes or Fidler's Ferry]. Owing to the rough weather (wind force 7), the Ant was taken into the shelter of the Dee Estuary and anchored in Wild Road off Mostyn.

While her crew were asleep, at about 3:30am, the Ant was struck by the SS Jane (Liverpool registered, owned Monk and Co.) which caused her to sink in a few minutes. The two on board the Ant were picked up by the boat of the Jane and landed at Llanerch y Mor.

A buoy was put to mark the wreck and was withdrawn by 1919 as the site was covered in sand. The site is now not shown on the HO chart and is listed as "dead".

Record of court case to establish responsibility for the collision:

DEE ESTUARY COLLISION

BARGE OWNERS' CLAIM:

Before his Honour Judge Shand,

sitting under Admiralty jurisdiction in the Liverpool County Court, on

Friday, assisted by Captains Thomas Pardy and John Trenery, as nautical

assessors, the owners of the barge Ant sought to recover from the owners of

the screw steamer Jane, £300 in respect of the sinking of the Ant by

collision with the Jane in Mostyn Roads, on the 19th February last. Mr. Segar

appeared for the owners of the Ant, and Mr. Alec Bateson for the owners of

the Jane.

The plaintiffs' case was that the Ant, which was a ketch rigged

vessel of 110 tons dead-weight, anchored through stress of weather in Mostyn

Roads, Dee estuary, on the 18th February. The Ant's captain, John

Waterworth, put out his riding light, but could not keep it alight, on

account of the violence of the wind. About half past one in the morning,

however, the master saw that the light was burning, and retired below with the

mate - the only other member of the crew - and went to sleep. The Jane struck

the Ant about half-past three. The latter sank, and both, the captain and

the mate, were rescued by the crew of the Jane.

Captain Waterworth also

maintained that the Jane was to blame for the collision for having attempted

to leave her anchorage in the roads by a course which afforded very little

room, when she could have gone by a wider and, therefore, safer course.

The

allegation of improper lookout was strongly denied by Captain David Monks,

master of the Jane, and he also asserted that the course he took in

leaving the roads was a perfectly safe one. The Ant had no light burning, and

was not visible to the lookout on the Jane.

The court expressed the opinion

that, having regard to the fact that the light on the Ant had blown out

several times, and that those on board had been unable to keep it alight, it

was a highly unseamanlike proceeding for the master and mate of the Ant to go

below and sleep, leaving nobody on deck with a light to warn any vessel on

emergency. The court found that a sufficient and proper look-out was kept on

board the Jane, to whose crew, they were of opinion that no blame was

attachable, and they gave judgment for the defendants, with costs.

Back to top

There are yachts moored at West Kirby and at Thurstaston during summer months.

The moorings are protected by sandbanks but at Spring High Tide, with strong

NW wind, considerable waves build up and can cause vessels to break free. They

are then dashed against the rocks on the Wirral shore.

Wrecks of leisure yachts driven ashore near Caldy by a storm

on 4 Oct 2009:

Now (2017) there is almost no sign of any wreckage in the sand below the

rocks near 53° 21.33'N, 3° 10.26'W.

Back to top

The approaches to the Mersey and Dee are strewn with sandbanks and in onshore winds there are breaking waves along the edges of the banks. Ships that were driven onto the banks were at the mercy of the waves and many lives were lost. The strong currents running between the sandbanks caused problems for sailing ships and when wind and tide were in different directions, steep waves build up in the channel. The approaches to the Mersey are especially dangerous in Northwesterly gales. The best way to rescue shipwrecked sailors was recognised to be by using small boats that could venture into the shallow waters around a stranded vessel. If such a boat could get upwind of the wreck and then anchor, by veering out line it would be possible to come to her assistance in a controlled way. The small boats used were of the type used as local fishing boats and gigs. They had sails that could be set when conditions allowed but they relied on a number of men aboard with oars. The men were usually local fishermen with experience of such boats and of the local conditions. To be out in storm conditions in these small open boats must have been terrifying but men to crew them were readily found.

The boats would have to be based at places where a boat could be launched from the shore in strong winds. In the Liverpool Bay area, this implied from within the more sheltered waters of the Mersey itself or from Hoylake, Formby or Point of Ayr which each had an inshore channel protected by an offshore sandbank except at the top of the tide. Such rescue attempts were not conducted by dedicated lifeboats until experience showed that this was the best and safest way.

Liverpool was the site of the first dedicated lifeboat station to be established anywhere in the world. This was at Formby in 1776 and was funded by the Dock Trustees. Subsequently a lifeboat station was established at Hoylake around 1803 and a lifeboat was kept at the mouth of the Mersey itself. The Dock Trustees were charged with responsibility for safety in the approaches to the Port of Liverpool. As a result of a formal inquiry into the state of lifeboats in 1823, it was recommended that four boats be provided: at Formby, Hoylake, Point of Ayr and the Magazines (near New Brighton). The lifeboat at the Magazines was established around 1827.

After the poor showing of the lifeboat service during the hurricane of 1839, the arrangements were changed and a later report in 1843 gave the situation as 9 lifeboats: namely 2 at Liverpool, 2 at the Magazines, 2 at Hoylake, 2 at Point of Ayr and one at Formby. The lifeboat service was now very efficient and saved very many lives. This was recognised in 1851 when the RNLI (named National Institute for Preservation of Life from Shipwreck at that time) awarded silver medals for outstanding bravery to the coxswains of all of these lifeboats. Each station had a permanent crew of about 10 men and boats were launched by carriage pulled by horses kept nearby. The crew were summoned by gun and it was claimed that the lifeboat could be under way in 17 or 18 minutes from receiving the signal of distress. The lifeboats had oars and sails, but to speed up rescue, an arrangement existed with the Steam Tug Company that as soon as a signal of distress was received, one of their tugs would proceed immediately and take the first available lifeboat from within the Mersey (i.e. Dock Board or Steam Tug Company lifeboat) in tow.

In 1858 the Mersey Docks and Habour Board took over from the Dock

Trustees the provision of 8 lifeboats at Liverpool, New Brighton,

Hoylake, Formby, Southport and Point of Ayr. From 1848 one of the

Hoylake lifeboats had been stationed at Hilbre Island.

This provided a direct access by a ramp to deep water at all tides.

Since the Liverpool Bay area was divided into

small numbered squares - the location of a wreck could be communicated

quickly to the lifeboat stations which were located close to the semaphore

signal stations at Gronant (Voel Nant); Hilbre Island; Bidston Hill and Liverpool.

The optical system of communication was replaced by an electric telegraph from

1861.

The Dee Estuary is mostly quite sheltered and vessels would anchor in Wild

Road (off Mostyn) or off Hilbre to wait for better weather. In a NW gale, at

high water on spring tides, substantial waves can build up in the Dee and

vessels can be driven from their anchors onto the sandbanks.

The entrance to the Dee Estuary had three lifeboat stations: at

Point of Ayr (beach launched from Gronant, then Talacre from 1894); ramp

launched from Hilbre Island and a beach launched lifeboat at Hoylake. The

service from Hoylake started in 1803 and continues to this day (all MDHB

lifeboats having been taken over by the RNLI in 1894) with a beach launched

lifeboat and a hovercraft. The Hilbre Island station (associated with Hoylake)

started in 1848 and ended in 1939. The Point of Ayr lifeboat was established

in 1826 and the last service was in 1916. There is a beach launched inshore

lifeboat at West Kirby (RNLI from 1966 on) and a mobile inshore lifeboat based

at Fflint (since 1957; RNLI since 1966).

The Fflint service was initiated by local people after a tragedy: on the night

of 26th December 1956, a Neston wildfowler was heard shouting as he struggled

in the fog-bound waters after being cut off by the tide. More details.

There were many services by these lifeboats. Most were to vessels aground on the outside of the Hoyle Bank or on the Welsh coast. There were some tragic losses of lifeboatmen:

Traveller

On 22 December 1810 there was a terrible storm. The vessel

Traveller, of Liverpool, was driven onto the Hoyle Bank [described as on Cheshire

Coast, 1 mile east of Hoyake and a few hundred yards from the shore].

An open boat was launched from the shore by local fishermen from the Hoylake

lifeboat crew. It got to sea safely despite huge waves pounding the

beach. They found no-one aboard the Traveller, and as the lifeboat crew

rowed around the stranded vessel, an enormous wave capsized the boat.

Of the lifeboat crew of ten, eight of them were drowned.

Newspaper reports.

More

details.

Lifeboatmen Lost: John Bird (40), Joseph Hughes (38), Henry

Bird (18), Richard Hughes (36), John Bird (16), Thomas Hughes (16),

Henry Bird (18), Nicholas Seed (27). The two saved were Thomas Fulton

and Thomas Davies.

Urania 1841. The Point of Ayr lifeboat, Robert Beck master,

attended the ship Urania

wrecked on the West Hoyle Bank. All passengers and crew (277) were

saved by the Point of Ayr and Hoylake lifeboats and several other local

vessels. Unfortunately the mate of the Point of Ayr lifeboat was struck

by the boom and drowned. A new mate, John Sherlock, was reported as

appointed in November 1841.

The Dock Committee [who paid for the lifeboat service] in a meeting

in December 1841 stated:

The widow of a man belonging to the Point of Ayr lifeboat, who had been

unfortunately drowned whilst going to a wreck, was presented with £10.

Rhyl lifeboat capsize

On 23 Jan 1853 the Rhyl

lifeboat Gwylan-y-Mor capsized with the loss of 6 lives. A vessel was